A Media Development Investment Fund Report

Index

- Preface

- Introduction

- Key Findings

- Lessons learned

- Don’t be the boss – a personal essay

- Myanmar’s independent media landscape

- Survey Results and Analysis

- Key decisions, momentous impact, lessons learned

- Status of outlets

- Operating media businesses on social media

- Emerging Platforms

- Post-coup revenue development

- Analysis of 10 MDIF media partners’ revenue

- Seizing opportunities during a crisis

- Turning to our audience for support

- Lessons in leadership

- The business of in-depth and investigative journalism

- A public service business model

- Looking Forward

- Afterward

- It’s never the right time – a personal essay

- Acknowledgements

- Methodology

- Suggested reading

- Survey questions

Always be curious and look beyond traditional business models.

-Senior Myanmar media executive

Preface

Even though the military junta is currently cracking down on VPNs, people are still taking risks and searching for news stories.

I’ve been thinking about an old film these days.

‘Jacob the Liar’

The film was released in 1999. It was directed by Peter Kassovitz and starred legendary actor Robin Williams as Jacob. The story was about Nazi-occupied Poland in 1944. In a Jewish ghetto, Jacob whispers to his fellow inhabitants the optimistic stories of allied forces advancing to save them.

He tells them he has a secret radio. Obviously, radios are strictly prohibited in ghettos. You can even be given the death sentence for having one. Yet by telling those stories, Jacob spreads hope across the ghetto and encourages everyone to continue each day. Jacob lies. But he makes people feel optimistic about the future.

When the German Gestapo learn about Jacob and his radio story, they tell him to confess that he doesn’t have a radio and that his stories are lies. This point is the climax of the film. If Jacob admits that he’s lying, he will live, but that will damage morale. If he refuses to tell the truth it could be at the cost of his life.

In the end, Jacob refuses to tell the truth and is shot and killed.

I was speechless at the end of the film. That was one of the films which made me continue my life as a journalist through the darkest times in my unfortunate country.

Right now in real life Myanmar, as soon as people wake up in the morning they grab their phones and look at the news using virtual protection networks. And they feel they still have hope. Even though the military junta is currently cracking down on VPNs, people are still taking risks and searching for the news and information they need. Yes, we’re living in the Union of the Republic of Ghetto where the news is our only daily essential vitamin.

Of course, we should not tell lies and we should not raise false hopes. According to our code of ethics, journalists should never fabricate information, and we should also not hide the truth. That’s why our job is difficult and why we must all be brave. That’s why we need moral and financial support.

So yes, we’re not Jacob the liar.

But we are Jacobs.

That’s why I’m sitting here in Yangon and still writing stories.

Because, simply, I’m also a Jacob.

Thit Ywet, Columnist, Yangon

Introduction

Whenever there’s a crisis, there’s an opportunity.

-Senior Myanmar media executive

The Business of Independent Myanmar Media Post-Coup: Experimenting with business models inside the country and in exile examines the ways in which independent media businesses have responded to, and been changed by, the 1 February 2021 military coup, and the business opportunities they have seized in its wake. It builds upon a report that MDIF published in November 2022, entitled The Business of Independent Media in Post-Coup Myanmar.

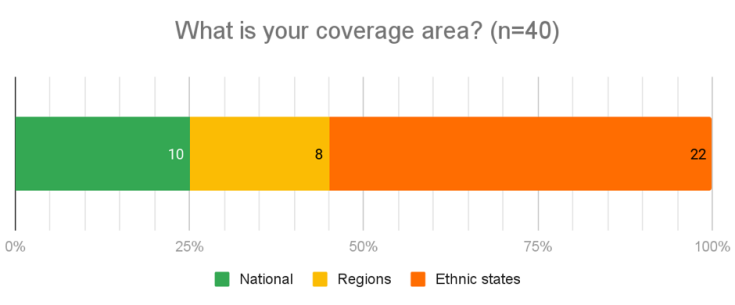

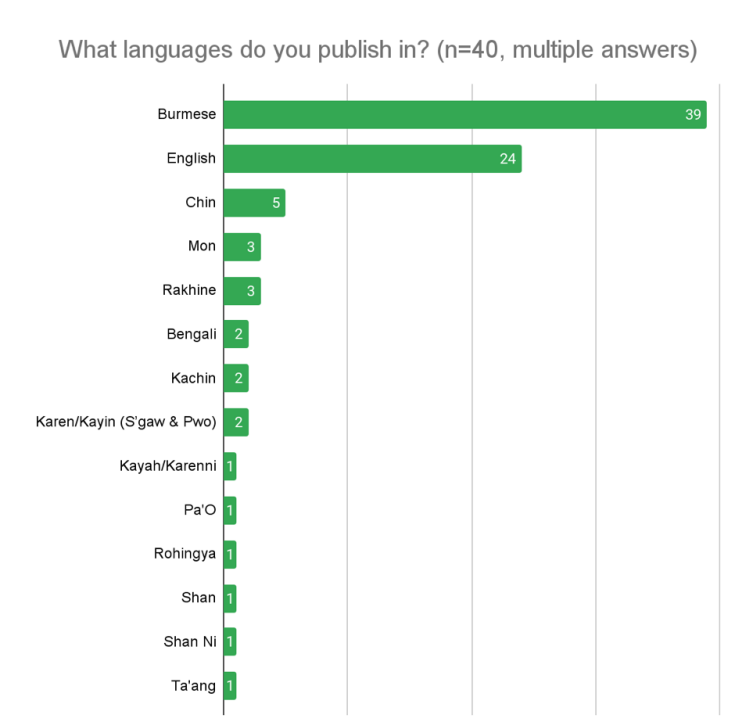

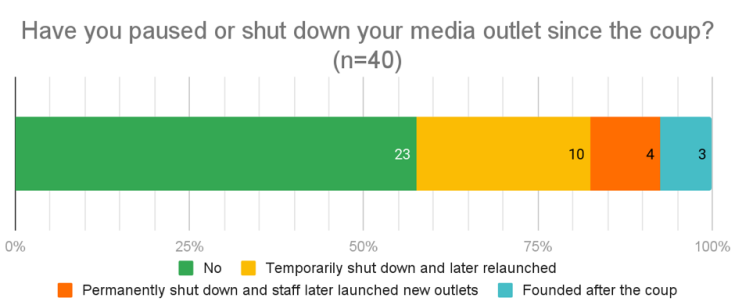

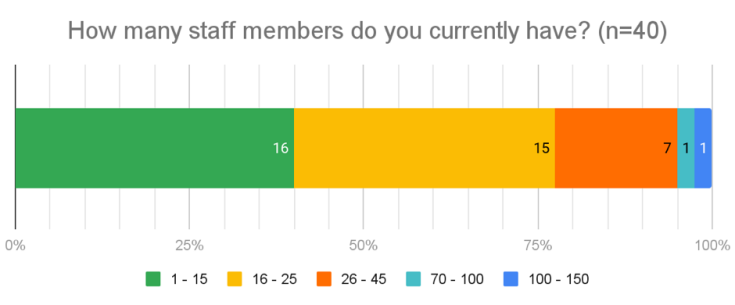

For this report, MDIF conducted survey interviews with senior executives of 40 independent media outlets. Together, they represent 10 national media, 22 ethnic media, and eight media from Myanmar’s regions1. Their operations vary in size: two are large (70-150 staff), seven are medium-sized (25-69 staff), and 31 are small (1-25 staff). Three of the outlets were launched in the wake of the coup; 22 were launched during the political opening period from 2011-2021; and 15 were launched during previous military regimes. Thirty-seven of these outlets were operating when the coup unfolded. Twenty-three have managed to keep operating with no interruptions, and 10 temporarily paused their operations and then started anew. Another four permanently shut down, but their senior team members subsequently launched new outlets. The remaining three outlets were launched post-coup. The 40 outlets surveyed collectively publish on multiple platforms and in 15 languages.

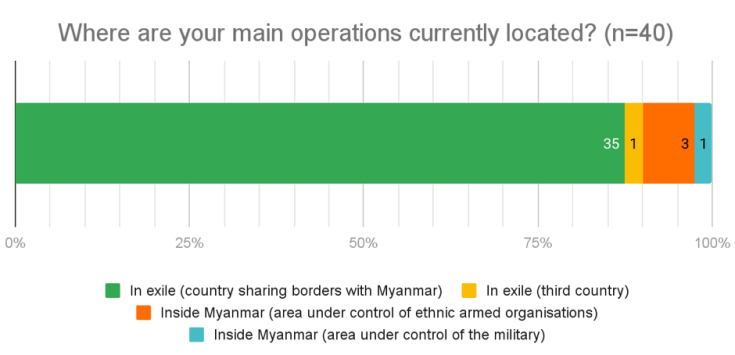

Most of the 40 outlets surveyed for this report have changed locations since the coup. Thirty-five have established their main operations in exile in countries bordering Myanmar, and one in a third country2. Only four have their operations inside the country: three in ethnic states under the control of ethnic armed organisations, and one in an area controlled by the military. Of the 35 outlets whose main operations are in neighbouring countries, six say they also have cross-border operations3, and three describe their operations as multi-country4. More than half of the outlets – 22 out of 40 – say they are in exile for the first time.

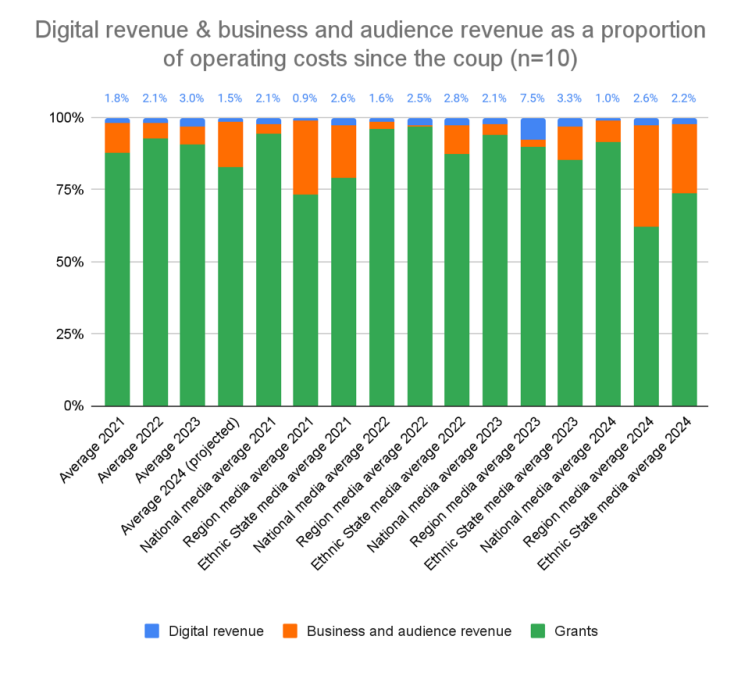

In June and July 2024, while conducting research for this report, most outlets surveyed were monetising at least one of their social media platforms, although for the majority the income earned was nominal. Almost all outlets say they currently depend on donor funding, partially or fully.

While not representative of all independent Myanmar media outlets, this report offers insight into a broad cross-section of the post-coup independent media world, including their audiences, sources of income, challenges, opportunities, lessons learned, and future priorities. To provide nuance and context for this data, four Myanmar media leaders share their experiences and reflections in personal essays, and an MDIF media business coach recounts his audience development and monetisation work with an ethnic media outlet. The ‘Operating media businesses on social media’ section provides comparative data, as well as insights into the complex business relationship between Myanmar media and the social media platforms on which they publish their content. The ‘Seizing business opportunities’ section highlights experimentation with a variety of revenue streams, including memberships, subscriptions and Public Service Announcements (PSAs).

1 Outlets covering Myanmar’s seven regions function primarily to serve the information needs of a particular geographic area; a large percentage of the population in these regions is composed of the majority Bamar/Burman ethnic group. Ethnic media outlets function primarily to serve the information needs of a particular ethnic minority nationality, including, but not limited to, the ethnic populations residing in Myanmar’s seven ethnic states.

2 In this context, third countries refer to countries that do not border Myanmar.

3 In this context, cross-border refers to media outlets that maintain some form of operations on both sides of a border. Some ethnic media, for example, have historically maintained cross-border offices in Myanmar and Thailand and/or India.

4 In this context, multi-country means the outlets have some form of operations and staff in multiple countries, although not necessarily an office.

Key Findings

We lost our pre-coup revenue streams and have become more donor reliant.

-Senior Myanmar media executive

Media management: Thirty-six of the 40 media outlets interviewed are currently running their operations in exile. Thirty-five are in neighbouring countries and one is in a third country. Of the four outlets still operating inside the country, three are operating in the ethnic states in areas controlled by ethnic armed operations, and one is operating in an area controlled by the military. Thirty-four of the 40 outlets have staff inside the country and also work with freelancers and/or citizen journalists; 5 only work with their own staff inside; and one outlet has no staff inside so is completely dependent on freelancers and citizen journalists. Key challenges include keeping staff safe, learning to effectively manage teams that are scattered in different locations, tackling human resource issues, including mental health struggles and staff mistreatment issues, including sexual harassment of women, and producing strong, independent journalism. Thirty-eight of the 40 senior media executives interviewed have pledged to keep their outlets running no matter what; the remaining two say if they do not receive additional funding very soon, they will need to close.

Audience Access, Growth and Engagement: As is expected during a crisis, all 40 outlets surveyed say they experienced significant digital audience growth in the wake of the coup, particularly in terms of Facebook followers. A steady increase in Facebook followers is, in fact, a common phenomenon around the world, yet the senior media executives also point to context-specific reasons: “We’re producing even more content than before the coup”, “Post-coup, our audiences are increasingly online and are more interested in news and information”, “The political situation has driven people online, even if it’s risky”, “We still have people on the ground so we’re able to produce the kind of content people want”, “Audiences are seeking out outlets they know and trust and that produce quality content”, “We’ve diversified our platforms and audiences”, “We’ve worked hard to rebuild our operations post-coup and to build new outlets”, “We’ve focused on community building and audience engagement”, “We understand our audiences better than before, and we’re developing strategic audience growth and engagement strategies based on metrics”, and “We’ve adopted platforms like TikTok to try to engage younger generations”. Close to half of the senior media executives interviewed noted that they now have stronger relationships with their audiences, and that their audiences trust and value them more than they did pre-coup.

Yet it’s also important to move beyond simple audience growth metrics to understand audience reach and engagement5 with content. Overall, as of 2024 the reach of many of the outlets surveyed is declining, with some variations.

For the eight outlets from Myanmar’s regions, for example, our research shows an upward trajectory that could be due to a variety of factors: increased conflict in Central Myanmar may have attracted greater interest in local media covering that area, and the fact that some outlets from the regions went underground and then launched new media that subsequently grew their audiences from zero may have resulted in rapid initial growth.

The data for the 22 ethnic media surveyed, on the other hand, shows erratic and slightly downward engagement since the coup, and for the 10 national media, downward engagement. While in some cases this may indicate they do not know their audiences as well as they should or are not giving them what they want, their audience engagement is likely impacted by a variety of external forces, including changing digital platform policies, and crises such as the military blocking Facebook after the coup, frequent and widespread internet shut-downs and, more recently, the crackdown on the virtual protection networks (VPNs) that audiences inside Myanmar use to access Facebook.

Another explanation is the change in Facebook’s algorithm6, starting in July 2022, that has prioritised entertainment and reduced the visibility of political content on news feeds. As a result, fewer people see news posts. People are also less likely to engage with news media, whether making comments about, or reacting to new posts, for fear of retribution from the military, even if they use pen names. When there is less interaction, Facebook shows posts to fewer people; therefore, this decrease in engagement makes it harder for news pages to reach their audiences. Little to no internet in more remote regions, and poor connectivity and slow speeds in other areas, can also have an impact on audience reach and engagement.

These are all potential reasons for a decline in audience engagement that interviewees have cited or that have been highlighted by our research, though a more in-depth study of each individual case would be needed to fully understand the current trend and its impact.

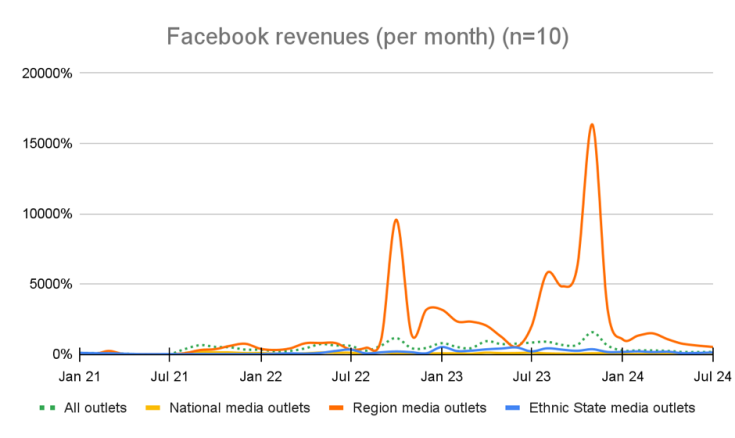

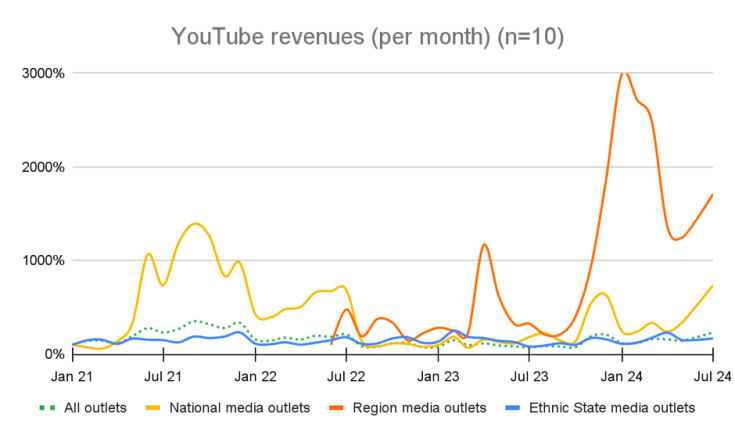

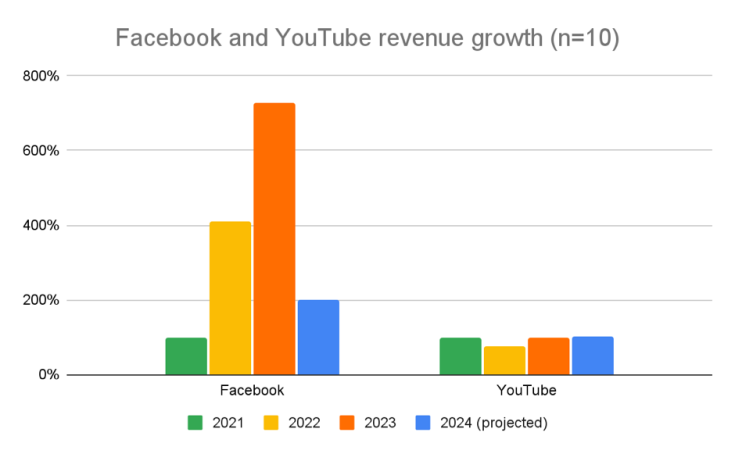

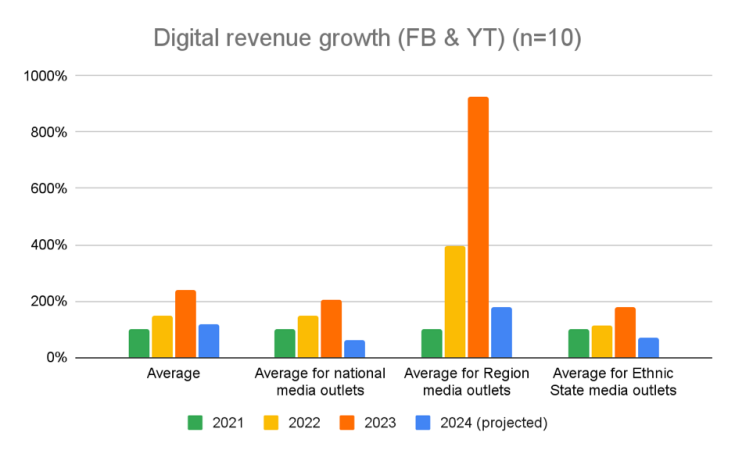

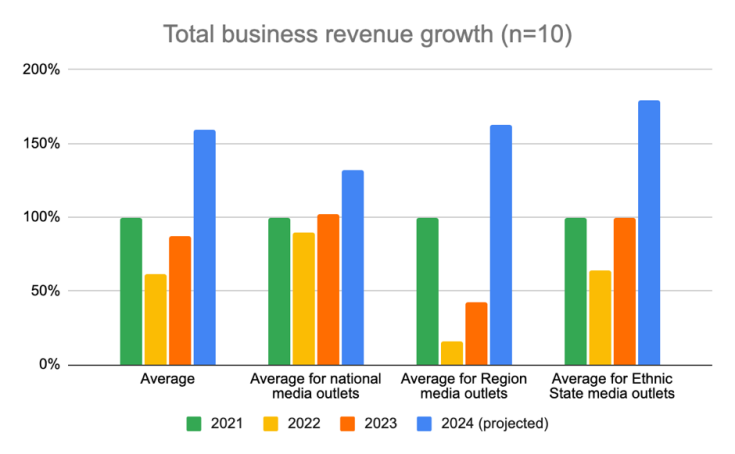

Sources of revenue7: In June and July 2024, while conducting research for this report, 25 of the 40 outlets surveyed were generating digital revenue by monetising their Facebook platforms, and 29 were monetising their YouTube platforms. Yet digital revenue monetisation has overall been unreliable and unpredictable in the post-coup period, and in 2024 digital revenues have fallen from their previous post-coup levels. In most cases, this is not because outlets are publishing less content; on the contrary, many outlets are experimenting with different forms of content and increasing the number of stories they publish. Yet, as outlined in the Audience access, growth and engagement section (above), there are external challenges they cannot control, including changes to platform policies, internet shutdowns, and the recent military crackdown on VPNs. The drop in revenues is linked, for example, to Facebook’s decision to change its algorithms at the end of 2023 to update its payment model for in-stream ads, replacing its previous CPM-based model8 with a performance-based system. Under the new system, content creators earn money based on the number of views their videos receive; this model favours popular content, and is thus a problem for creators with smaller, niche audiences. These two decisions resulted in a significant drop in revenues in late 2023 and subsequent monthly declines, with occasional modest increases. In addition, since the coup YouTube does not pay for views by audiences inside Myanmar, so media outlets can only monetise this platform by focusing on diaspora audiences. This tends to favour ethnic media since some already have significant diaspora audiences.

While continuing digital monetisation efforts, many senior media executives say they are also exploring other revenue opportunities. For example, 13 outlets earn revenue from their audiences: eight from donation initiatives; three from membership programs (one was launched before the coup and two afterwards); and two from subscription services (one national outlet and one outlet from the regions). Yet all of these revenue streams require consistently high quality content and a core loyal audience so are not currently viable options for all media outlets.

Building upon the skills and knowledge acquired from MDIF’s PSA Initiative, 14 of the 40 outlets surveyed now earn revenue from PSA partnerships with other organisations. Three outlets also earn modest advertising revenues from collaboration with small businesses in the ethnic states in areas controlled by ethnic armed organisations; senior executives say they expect these collaborations will grow. Two outlets also sell content to national and international outlets, and many other outlets participate in a wide variety of editorial collaborations.

Donor funding: Almost all of the 40 senior media executives interviewed say they continue to depend on grants, either partially or totally. Thirty-nine out of 40 say they have received some form of grant since the coup. Thirty-three also say they have at least one current grant; 19 of the 33 add, however, that their current grant is small and short-term. The executives note that international funding opportunities started decreasing in 2023, and that 2024 has proven to be extremely challenging; this is in large part due to the significant periods between one grant ending and a new one beginning, and uncertainty as to which outlets will receive new grants. Another challenge is that available funds are mostly short-term and one-off, and often tied to content production. They say that what is most needed are long-term, unrestricted funds to cover their core operational costs.

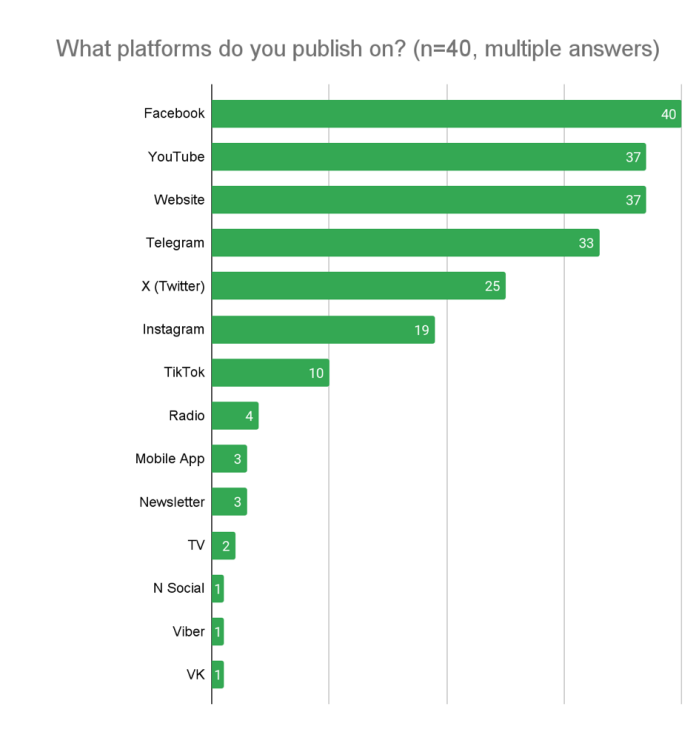

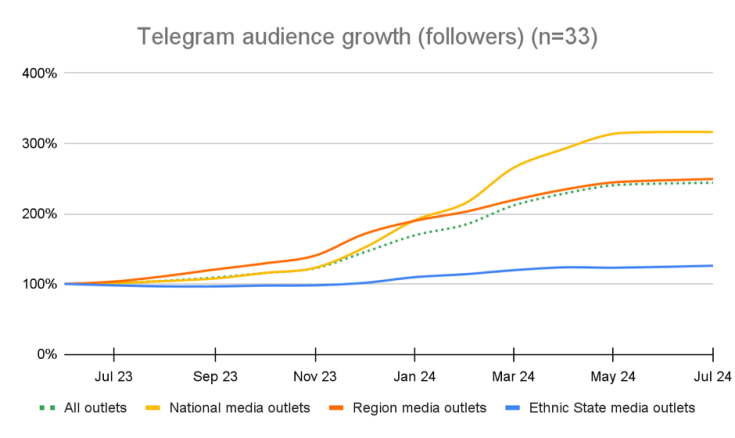

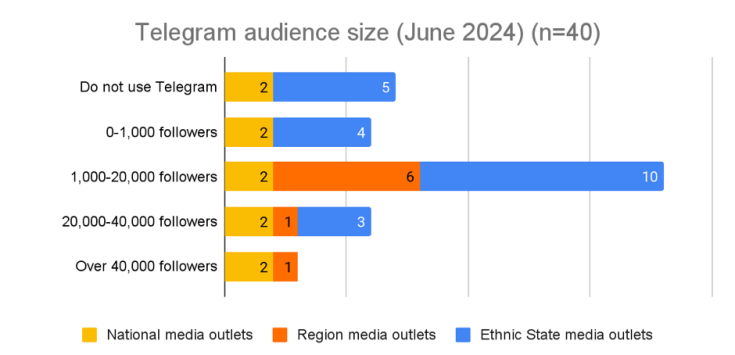

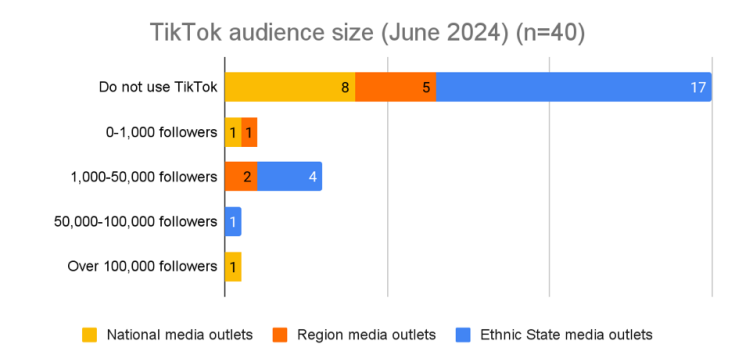

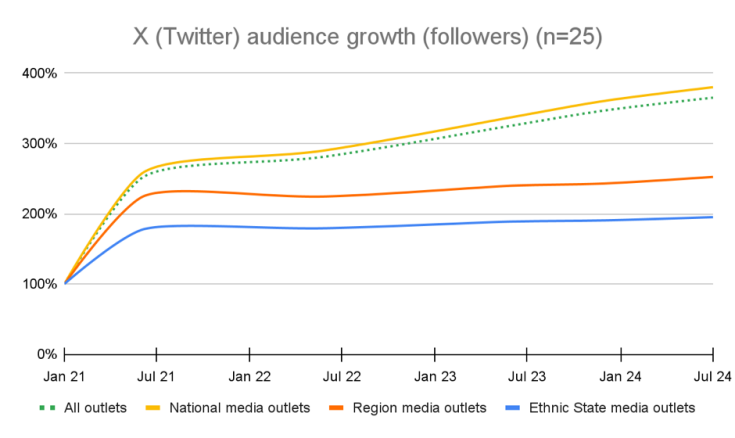

Digital platform development: In response to the crackdown on VPNs and Facebook access inside Myanmar, and the fact that YouTube policies do not currently allow Myanmar media to monetise their audiences inside the country, many of the surveyed outlets are currently working to diversify their platforms with a view to growing and diversifying their audiences. After Facebook and YouTube, Telegram is arguably the most popular platform, with 33 of the 40 outlets surveyed setting up accounts post-coup. Ten of the 40 outlets have also set up TikTok and Instagram accounts and 11 outlets, X accounts, in an effort to diversify their audiences, including attracting younger generations. Yet a closer look at the data indicates that while they’ve established a presence on these platforms, in many cases they are not yet very active. In addition, at least four outlets have set up new offline platforms, such as FM and shortwave radio stations, to reach audiences in more remote areas that have limited or no internet access. All 40 of the outlets surveyed are currently on Facebook, 37 are on YouTube, 37 have websites, 33 are on Telegram, and 25 are on X. Yet due to the military’s actions to restrict, or prevent, public access to independent news sources, growing and diversifying audiences remains a challenge.

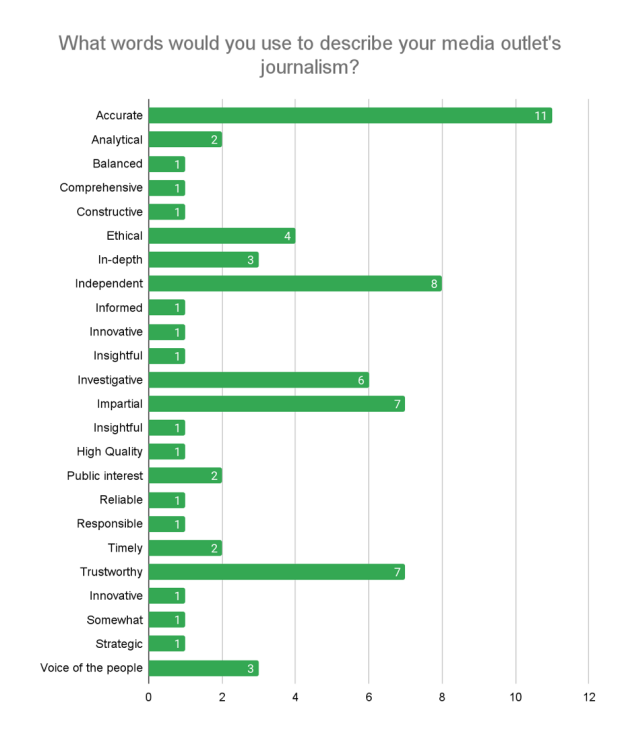

Journalism: The senior media executives interviewed for this report say they understand that producing quality journalism is vital for their brand, whether in terms of how they are viewed by their audiences, their ability to attract donor funding and other partnerships, or their efforts to monetise their digital platforms. Some say it is one of their biggest lessons learned since the coup. They also seem keenly aware of the widespread view that Myanmar journalism has been struggling since the start of the coup in terms of its independence and impartiality, particularly vis-à-vis the resistance. Yet only one of the 40 senior media executives interviewed described their journalism as “somewhat independent”, due to their struggles to do independent and impartial coverage of the resistance, as well as their post-coup dependence on donor funding. The other 39 senior media executives variously describe their outlets’ journalism as professional, independent, ethical, trustworthy, accurate, reliable, impartial, balanced, in the public interest, timely, strategic, in-depth, investigative, innovative, insightful, constructive, and comprehensive. A more indepth study is needed to determine whether or not these words provide an accurate picture of the current state of their individual journalistic efforts. Meanwhile, veteran media journalists, trainers and observers say they are aware of efforts to improve professional and ethical journalistic standards, and to instil a greater understanding of what it means to be an independent journalist during a time of crisis. But they caution there is still much to be done. More extensive and comprehensive coverage of Central Myanmar and a growing desire to do in-depth and investigative journalism are two other noteworthy post-coup journalistic trends.

Looking ahead: More than three years after the coup, a significant majority of the 40 senior media executives interviewed for this report say they are still dependent, partially or fully, on grants to run their operations. While they cannot control the external factors impacting on their work, be that the conflict or the unpredictability of digital platform policies, they recognise that if they want to survive and attract funding and revenue, they need to build strong, professional operations and to prove their resilience. That includes doing independent, ethical journalism, developing strong financial management and inclusive HR policies, engaging with their audiences, experimenting with diverse revenue streams, planning for the future, and preparing for the unexpected.

5 Audience engagement on digital platforms refers to users’ interactions with content, including likes, shares, comments, clicks, follows, and participation in polls or contests. It measures how actively users interact with and respond to the content.

6 An algorithm is a ranking system that uses machine learning to arrange content in users’ feeds, prioritising and personalising posts based on user behavior, preferences, and engagement patterns with a view to showing the most relevant content.

7 MDIF uses three categories to define revenue: 1. business revenue, generated from services provided to third parties, such as commercial advertisements and PSAs, conducting training and events, and content production; 2. Audience revenue: revenue generated from the media’s audience, for example through membership, subscriptions and donations; 3. Digital revenue: revenue generated from monetising platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, etc.

8 CPM means Cost Per Mille (or) Cost Per Thousand impressions

Lessons Learned

When partnering with international organisations, strong money management is key.

-Senior Myanmar media executive

Innovate: “Be curious and don’t depend on traditional business models.” Many of the senior media executives interviewed say they have tried to access funding and to generate digital revenue, but that both sources are unpredictable and uncertain. They have therefore come to understand that if they want to survive, build their media businesses, and diversify their revenue streams, they will need to be more creative, to experiment, and to take greater risks.

Never stop strengthening your digital skills and know-how: “I wish we hadn’t resisted going fully digital before the coup.” All of the 40 outlets surveyed are now digital first, and say they’ve learned that without strong digital communication skills they cannot survive. For the outlets that resisted this move pre-coup, it has been a tough lesson learned. All 40 senior executives interviewed say they have invested in digital skills development since the coup, either in-house or with the assistance of external organisations. They also say they have adopted new digital platforms and developed new content forms.

Put your audience first: “During a crisis, people turn to independent journalism, so it is a good time to engage with your audience, build their trust, and seek their support.” Media executives say they have learned that audiences are at the core of their businesses and are key to revenue generation. A key lesson is that they need to be able to monitor and analyse their audience metrics in order to develop strong audience growth and engagement strategies.

Diversify your platforms: ”We’ve started using TikTok because that’s where the audiences are, especially young people.” Faced with unstable social media platform policies and on-going internet shutdowns, VPN crack-downs and other audience inhibitors, a significant majority of the 40 media executives interviewed say they have made efforts to diversify their platforms since the coup.

Be smart about money: “Since the coup we’ve realised that if we want to run a professional operation we need revenue and funding.” The senior executives point to the importance of wise and ethical money management, and say they have learned that it is the only way to establish a good reputation and to attract funding. They also caution not to over-extend your operations; for example, if your funding is not guaranteed and you do not have it in hand, then do not expand your operations or hire more staff.

Instill professional management practices: “We should have built a stronger organisation when we had the chance and when our lives were more peaceful.” All of the senior executives point to the importance of building strong, professional operations, including taking care of their staff and being respectful towards them, and being honest, transparent and inclusive with regards to decision-making.

Build strong and transparent partnerships with donors: “Don’t over-promise to donors in a crisis situation, because you may be overwhelmed with many other things and tired and unable to deliver.” Almost all of the media executives say they need donor support to survive and build their operations. Those that did not have a lot of experience dealing with donors in the pre-coup period say they have faced a steep learning curve and that it has made things more difficult for them. They stress the importance of establishing a relationship of trust with donors and being able to demonstrate their resilience and professionalism, both with regards to their organisational and financial management and their journalism.

Do trustworthy, independent journalism: “Producing high quality journalism will help to protect you and your reputation. Without it, you will lose everything.” In the wake of the coup, much of the content being produced by independent media was viewed as partisan, pro-resistance, and revolutionary. Senior media executives have learned a hard lesson that they need to protect their journalism and always maintain high standards. With hindsight, some say they wish they had spent more time in the pre-coup period coaching their staff, especially the younger generations, about the role of journalism.

Build strong support networks: “Networks help you stay safe.” The outlets surveyed that are part of networks stress the important role they have played since the coup. Those that are not part of networks say that if they had been they would be much stronger now.

Never abandon your ethics: “When times are tough it can be challenging to maintain ethical values.” The need to always uphold your ethical values and mission has also been a tough lesson for many senior media executives. Ethics cannot be set aside during a crisis. Once lost, they say, so is your reputation and it is hard to get it back.

Be prepared: “Don’t under-estimate anything and always have a Plan B.” All 40 senior media executives say they have learned that change comes quickly and unexpectedly, so in order to survive, you always need to be ready to react quickly and to be flexible.

“Don’t be the boss” – a personal essay

We all know and respect each other, and that’s why our team can always move forward.

I flew to Thailand in mid 2021 with my Myitkyina News Journal colleagues to seek refuge from the devastating consequences of the military coup. It was a heart-breaking move, but we took solace in the fact that we could once again meet up with our Chief Editor Seng Mai.

Seeking urgent medical help, Seng Mai had left Myanmar in April 2021 right after the coup to set up a new life in Thailand. Early the next year, as we were preparing to flee to exile in Thailand, she was preparing for a more permanent move to Australia.

During her time in Thailand Seng Mai had continued to lead the editorial side of our operations. In the immediate wake of the coup, she had also contributed to our difficult decision-making and preparations for exile.

Our team has always been very close, so the reunion in Thailand was an emotional one. Afterwards, Seng Mai flew to Australia and we flew north to set up our own new lives in Chiang Mai.

The next time we saw each other in person was in November 2023 when Seng Mai was feeling better and able to travel back to Thailand. That was also an emotional reunion, especially since this time I was preparing for my own gut-wrenching move to the USA.

Seng Mai and I co-founded MNJ in Myitkyina, Kachin State, in 2014, during our country’s heady political opening period. Ten years later, from far-flung countries, we continue to co-manage the MNJ team online. Despite the huge geographical distance between the two of us and the team, and the challenging time differences, we manage to make it work.

When the coup happened, Seng Mai and I sat down with our team, in person and virtually, and had an honest discussion about what to do. We really wanted to stay in Kachin State, but when some of our team members were detained, we realised we weren’t safe. Each team member was given a chance to make their own decision about staying or leaving. It was tough, but the team was very supportive. We think that’s one of the reasons our media business has survived, even though we’re no longer all physically together. We’ve been honest and supportive from the start, and we trust each other.

We also think our shared management style has something to do with it. I’m the CEO and Executive Director and Seng Mai is the Chief Editor, but our motto is ‘don’t be the boss and don’t be bossy’. We all know and respect each other and that’s why our team can always move forward. In Thailand, we eat, live, sleep and work in the same compound, whatever our jobs. Some team members’ families also stay with the team. That was my life until I left for the USA. Our team members knew about Seng Mai’s health issues, and her planned moves to Thailand and then Australia. They also knew about my plan to move to the USA. We made sure we had open discussions about everything.

COVID also helped to prepare us for the online life that we’re currently living, although admittedly we stayed loyal to print until we were forced to give it up when the coup happened. It was only at that point that we finally embraced online 100%. And we’re still learning all of the time and improving our skills. We’ve had no choice – our media business depends on it. Luckily Signal is a secure platform so we can hold online daily, weekly and monthly meetings, and correspond in teamwide groups. That way we make sure everyone knows what’s going on all of the time.

Of course, having the two top managers far away has changed the way MNJ is operating. Chiang Mai remains the hub of our operation, and since my departure, our main editor Sithu Aung is now in charge of the hub, and other team members have had a chance to step up and to assume greater responsibility for our operations. The Chiang Mai team also oversees finances on the ground.

From a journalism point of view, Seng Mai continues to worry about the challenges presented by the dire situation inside the country, including developing reliable sources on all sides and remaining independent and balanced. Luckily, trusted senior reporters and trainers continue to assist our team and to monitor our work. This is both helpful and inspiring.

Seng Mai and I think these changes are in many ways good for our operation and make us more resilient. And our supporters appear to think the same thing. They’ve visited our team in Chiang Mai and seen how things function in person, and they’ve continued supporting us. It’s proving challenging, however, to focus on business development. We get support from an MDIF coach, but at the moment we don’t have any business income. Even though our digital audience has grown significantly, for example, we’re only currently able to make a tiny bit of money from our YouTube platform. That is worrying.

Seng Mai and I also continue to struggle with our new lives in our different countries. In my case, I need to also work at another job so my family has enough money to live. Before the coup, I only had to concentrate on MNJ. Now I’m forced to learn how to juggle.

Like everyone else working in the independent Myanmar media sector, I guess we’ve accepted that our new lives have brought with them many challenges. Yet Seng Mai has already been working virtually for three years, and I’ve been doing the same for more than one year. So we’ve already put our new virtual management model to the test and we’re determined to keep going.

Brang Mai (CEO and Executive-Editor) and Seng Mai (Editor-in-chief), Myitkyina News Journal

Myanmar’s independent media landscape

Given our increased dependence on donor funding and our ongoing struggles to ensure our journalism isn’t aligned with the resistance, I would describe our outlet as somewhat independent.

-Senior Myanmar media executive

There are a multitude of diverse private media outlets operating in the current Myanmar media landscape, including national media outlets and local media outlets from the county’s ethnic states and regions. There is no up-to-date research data publicly available as to the number of these outlets, yet based on research and interviews, as well as an in-house online assessment, MDIF estimates there may be as many as 80 to 100 outlets that are currently active.

The words private and independent are often used interchangeably to describe these outlets. Private, however, refers to non-state ownership, whereas criteria used to assess independence is more complex. It can include ownership, supporters and investors, political ties, editorial stance, policies, ethics and content. According to the Independent Press Council Myanmar, independent outlets must not have ties to the junta, armed groups, political groups or businesses9, and must have an editorial process and a strong newsroom structure. Some people also use the term ‘public interest media’ to describe these outlets.

A significant number of the aforementioned private media outlets are either viewed as independent or self-define as such. Yet given the complexity of the Myanmar media environment and the state of conflict, as well as their own professional struggles, they may not meet all of the criteria all of the time. As such, independence is not a black and white issue. Numerous Myanmar media outlets have struggled to maintain their editorial independence and to resist influence from resistance factions, as well as their own desire to support the revolution. This means their understanding of the role of independent media has been tested.

All of these outlets have had to operate in an unpredictable and unsafe environment, The first six months of 2024 alone provide a chilling picture. On 10 January, the 50-year-old documentary filmmaker Shin Daewe was sentenced to life in prison under the Counter-Terrorism Act for ‘funding terrorism’. On 31 January, the journalist Myat Thu Tan was shot and killed while in military custody in Mrauk-U in western Rakhine State. On 28 June, Development Media Group reporter Htet Aung was sentenced to five years in prison with hard labour, along with the outlet’s guard Soe Win Aung; both were charged under Section 52(a) of the Counter-Terrorism Law. These are just three of many tragic stories that illustrate the junta’s ongoing efforts to try to crush independent media actors.

According to a 2024 report by the International Center for Not-For-Profit Law10, journalists from an estimated 90 media outlets have been detained since the coup, and close to half of them have also been convicted and imprisoned. The military has also censored outlets, raided their offices, seized assets, revoked licenses11, banned outlets, blocked the internet, and committed many other acts of violence.

The widespread crackdown on free expression and association has also affected 14 additional outlets, making the total 104. As the 2015 Broadcasting Law was never passed, there were only two independent broadcasters when the coup took place – Mizzima and DVB – operating on channels licensed by the state media. Those agreements ended in the wake of the coup, and the military’s 2021 amendment of the Broadcasting Law threatened people working for unlicensed outlets with up to five years’ imprisonment. The junta’s 2023 amendment of the Printing and Publishing Law (2014) gave them full control.

Half of the journalists detained were working for national outlets, and the other half for local media outlets from the ethnic states or regions; more journalists from regional outlets were detained than from ethnic outlets. A small number of detained journalists also worked for international outlets. At least half of the journalists detained were working for media outlets that had moved into exile. Many detained journalists worked for outlets that were viewed as pro-resistance; a small number worked for pro-military media, including state media.

According to ICNL’s research, 160 journalists have so far been charged with crimes, including incitement, “false news”, and counter-terrorism, with prison terms as long as 20 years. At least five journalists have been killed12. When a team member is detained or killed, it has a serious impact on their outlet legally, financially, emotionally, and in terms of safety. Since the coup, the military has also increased surveillance and communications interception, including online harassment and intimidation.

9 ICPM is referring to military or crony owned businesses.

10 ICNL used a broad definition of “journalist” in accordance with international standards, including individuals associated with “pro-military” media, including state media.

11 7Day, DVB, The Irrawaddy, Khit Thit Media, Myanmar Now, Mizzima, Tachileik News Agency, Myitkyina News Journal, The 74 Media, Ayeyarwaddy Times, Delta News Agency, The 74 Media, Zayar Times News Agency, Kantarawaddy News Agency, Mon News Agency.

12 Pu Tuidim, founder of the Chin news agency Khonumthung; Sai Win Aung, editor of the Federal News Journal; Soe Naing and Aye Kaw, freelance photojournalists, and Myat Thu Tun, reporter for the Rakhine outlet Western

Survey Results and Analysis

You can’t afford to lose your audience’s trust and your credibility, as then you’re finished.

-Senior Myanmar media executive

Based on in-depth survey interviews with 40 senior media executives, the 36 charts in this section explore the post-coup reality of independent media outlets, including operational status, locations, platforms, languages, coverage areas, staffing, operating budgets, digital audience growth, digital investment, revenue and grants, the challenges associated with operating media businesses on social media platforms, new opportunities, and future priorities.

This first section provides an overview of the outlets surveyed, starting with key decisions, momentous impact, and lessons learned.

Key Decisions

We decided to move to exile, knowing we may never go back.

-Senior Myanmar media executive

The key decisions cited by the 40 senior media executives interviewed point to five main themes: keeping our team safe, not leaving, going into exile, continuing our work, and committing to independent journalism.

Keeping our team safe

- “Committing to protecting our team.”

- “Respecting people’s right to stay or leave.”

Not leaving

- “Deciding to keep operating our outlet inside our country.”

- “Staying inside, even if it meant less donor support.”

- “To ensure we know what’s going on, keeping some team members inside the country.”

Going to exile

- “Deciding to go underground and then moving to exile.”

- “Moving to exile, knowing we may never go back.”

- “Relocating our team to a third country.”

- “Moving our senior staff to exile.”

- “Moving some staff to exile to ensure they were safe.”

- “Moving to exile with no financial support.”

- “Relocating to exile and leaving everything behind.”

Continuing our work

- “Shutting down our outlet and launching a new one.”

- “To ensure our survival, changing our focus post-coup and rebranding.”

- “Continuing our work, even if it would have been easier to stop.”

- “To ensure our survival, letting staff go.”

- “To keep going no matter what.”

- “Relocating to the border.”

- “Keeping moving.”

- “Setting up a news agency.”

Committing to independent journalism

- “Committing to doing professional journalism.”

- “Staying independent.”

- “Endeavouring to be balanced.”

- “Insisting everything is checked and verified before publishing, even if that is difficult and time-consuming.”

- “Publishing our stories despite threats.”

- “Supporting the work of citizen journalists.”

Momentous impact

“We lost our pre-coup revenue streams and have become more donor reliant.

-Senior Myanmar media executive

With regards to impact, the senior media executives say that the areas of their work that have been most affected, whether positively or negatively, are linked to safety and security, finances, audiences, teams, and journalism.

Safety and security

- “We had to go underground.”

- “We had to relocate many times.”

- “We had to go into exile.”

- “Our office was raided and our equipment confiscated, so we had to start all over again.”

- “Our staff has been threatened, arrested and detained.”

- “We feel unsafe physically and mentally.”

- “We can’t work freely and safely the way we used to.”

- “We have to hide our identities inside our country and in exile.”

- “There are ongoing military threats.”

- “We’ve lost the right to live in our homes and country.”

- “We’ve been forced to live illegally in a different country.”

Finances

- “We lost our pre-coup revenue streams and have become more donor reliant.”

- “We’re financially insecure.”

- “We don’t have enough resources to support our operations.”

- “We can’t generate the same revenue as before.”

- “We’ve been forced to transform ourselves into a different media outlet.”

- “We’re unable to pay proper salaries.”

- “We’re being forced to work other jobs to support our outlet.”

- “We decided to relaunch our old media outlet.”

- “We decided to set up a news agency.”

Audiences

- “Our audiences have grown and diversified, and they trust us more.”

- “Our audiences want to support us.”

- “People are more interested in independent news than they were before the coup, including young people.”

Teams

- “It’s hard not being together in the same place with the whole team.”

- “We don’t have enough resources to relocate all of our staff.”

- “We all feel greater pressure and responsibility.”

- “Team members are suffering mental and emotional distress.”

Journalism

- “We lost the right to report freely and safely.”

- “We don’t have freedom of expression or free media inside our country.”

- “We’re unable to work the way we used to, whether that be news gathering on the ground, collecting high quality video footage, in-field research, reporting or investigations.”

- “We’ve been forced to change the way we do news.”

- “We’re no longer on the ground where the news is happening.”

- “We lost trusted sources.”

- “We can’t cover our community the way we used to.”

Lessons learned

When times are tough, you have to protect your ethical standards

-Senior Myanmar media executive

The senior media executives point to many lessons learned over the past three years linked to eight areas: finances, staying safe, audiences, journalism, communication, digital space, organisational development, and rapid response.

Digital Space

- “Digital and technology skills are vital.”

- “We should have focused more on the digital side of our operations before the coup, instead of focusing on print. It would have been more useful.”

Finances

- “Before the coup, we didn’t really think about money. But since the coup we’ve realised that if we want to run a professional operation we need support.”

- “We didn’t have a lot of experience dealing with donors in the pre-coup period, and we now realise that that is making things more difficult now.”

- “Don’t over-promise to donors in a crisis situation, because you may be overwhelmed with many other things and tired and unable to deliver.”

- “Don’t expand your operations and hire new people unless you’re absolutely sure you have funding.”

- “When partnering with international organisations, money management (accuracy) is key.”

Staying Safe

- “Staying safe is more important than anything else.”

- “Before the coup, we weren’t aware of the risk. We were just preoccupied with running our operations. We only had a Plan A – not a Plan B or C. Now we are wiser and know we always need to be prepared for this kind of crisis.”

- “Best to be mobile and flexible rather than having everything in one place, as you are less vulnerable if raided.”

- “Try to be as legal as possible when you’re in exile.”

- “We’ve learned that we can’t always trust or predict what will happen inside our country, Therefore even if we have a chance to go back and work inside, we’ll still maintain an office in exile as a precaution and protection.”

- “You have to be ready to move to stay safe.”

- “Networks help you stay safe.”

- “Things can always get worse. You have to be prepared.”

- “We can’t trust the military, even when it’s a so-called peaceful period. You have to be ready, always watching and ready to react.”

- “We’ve learned the hard lesson that you always have to have a Plan B so you’re prepared for a crisis.”

- “We can never trust that our country is truly moving toward democracy and peace. We need to be more careful, to always monitor the situation, and to be ready for crises.”

- “During a crisis it is challenging to try to keep people safe, to help them as much as you would like, and to manage them when they’re all scattered in different places.

Communication

- “Given technology, it is possible to continue working together wherever we are.”

Organisational Development

- “We should have built a stronger organisation when we had the chance and when our lives were more peaceful; it’s tougher to do that now.”

- “It’s always better to be physically close to your team. Managing from different places and time zones is very challenging.”

- “If you don’t have proper institutional policies it can lead to a lot of misunderstandings and the loss of staff.”

- “Teamwork and mutual understanding is key to survival during a crisis.”

Journalism

- “Producing high quality journalism will help to protect you and your reputation. If not, you lose everything.”

- “We didn’t collect a lot of footage about life before the coup, and we now realise how important it is to do that.”

- “During a crisis, people turn to independent journalism.”

- “You always need to distinguish between journalism and activism.”

- “You have to closely monitor journalism quality and to remind people what it means to be a journalist during a crisis.”

- “You need to have conflict-sensitive thinking when doing reporting, as your decisions can affect many people and sometimes place them at risk even when that’s not your intention.”

- “Since the coup so much information is manipulated, so we need to check everything.”

- “We always need to distinguish between journalism and activism – even people who have spent their lives working as journalists.”

- “During a crisis, you risk losing access to your platforms and important information during a crisis, so need to archive everything.”

Rapid Response

- “To survive, you always need to be ready to react quickly and to be flexible, whether faced with unfamiliar situations or crises.”

- “Things can change very quickly.”

Audiences

- “You can’t afford to lose your audience’s trust and your credibility, as then you are finished.”

- “You have to remain relevant.”

- “We can educate our audiences by producing public service announcements.”

Status of outlets

We’ve developed our organisation, including instituting professional policies and strengthening our team in terms of numbers and capacity.

-Senior Myanmar media executive

This second section introduces the 40 outlets surveyed for this report. To start off, a series of 11 charts cover their targeted remit and coverage areas, platforms, languages, locations, staffing, journalism and current operating budgets.

The first two charts look at remit and coverage. Ten national outlets, eight outlets from the regions, and 22 ethnic outlets were surveyed. The ethnic media far outnumber the national outlets and the outlets from Myanmar’s seven regions. There are a variety of reasons that help to explain why there are so many ethnic media outlets: many of the longstanding ethnic media are members of the Burma News International network and this has helped to ensure their survival and resilience; they have a long history and have had a lot of support over the years; they want to ensure their individual ethnic groups have a voice in their own languages; and the ethnic regions have not always had substantive coverage due to their comparatively remote locations, local languages, sensitivity, and conflict. By comparison, it is easier for national media to cover the country’s seven regions, whether geographically, linguistically (the main language is Burmese), culturally (the dominant population is Burman/Bamar), or politically. As well, although some of the media outlets from the regions were founded by experienced journalists, the regional sector only started developing during the political opening period and is therefore collectively less experienced.

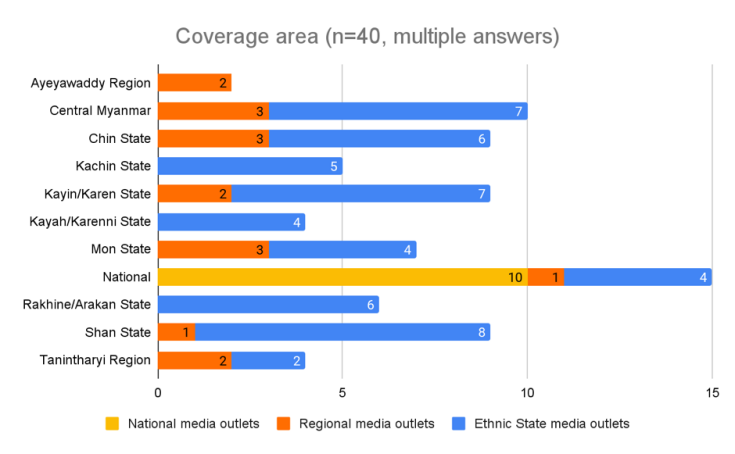

The second chart shows the number of media surveyed doing national coverage versus coverage of the ethnic states and regions. The national media line, for example, includes all of the national media outlets, but also some ethnic and regional media that say they also do national coverage. The same is true for coverage of Central Myanmar (Sagaing, Mandalay, Bago and Magway Regions) and some of the ethnic states; for example, some national outlets say they also cover specific regions and ethnic states, while some ethnic media also cover certain regions where their ethnic groups are also located.

The next chart shows the platforms on which the senior media executives say their outlets currently publish. Not surprisingly, Facebook remains the most important platform for publishing news and information, followed by YouTube. Despite the fact that in the post-coup period YouTube does not allow media outlets to monetise their audiences inside Myanmar, the data in this chart indicates that the platform nonetheless remains very popular. One of the reasons is that, unlike Facebook, audiences can access news on YouTube without using VPNs; in light of the crackdown on VPNs inside Myanmar, this is vital. The use of Telegram has grown significantly since the coup, especially since 2023, and more recently in response to the crackdown on VPNs inside Myanmar; none of the media were using the platform before the coup and 33 are now on it, although some are not very active. It is also relevant that since 2024 Myanmar media outlets have the potential to monetise their Telegram platforms. Although a large number of senior media executives say they have websites, that platform is rarely as active as their social media platforms. Please see the revenue section (later in this report) for more information.

Although only two of the outlets say they publish newsletters, this is a popular trend in other parts of the world so may see further growth among Myanmar media. Also, while the next chart indicates that only four media have radio stations and two, television stations, many other outlets also produce radio and television content.

Many media are diversifying their platforms in an effort to expand their reach and sustainability, yet in reality many of the outlets are not very active on all of the platforms they cite. In the post-coup period, for example, many have opened accounts on Instagram and TikTok, but based on our research some are not active. Several executives referenced TikTok as the place where audiences are; some also want to publish their content there in an effort to counter the devastating levels of misinformation and disinformation. In addition, the TikTok algorithm works well compared to Facebook, so this means the outlets can more easily reach a larger audience. Nonetheless, some executives say they worry about platform ownership. For example, the CEO of TikTok is Singaporean but the majority of shareholders are Chinese. With headquarters in the UAE, Telegram is owned by Russian entrepreneurs. Telegram also has a reputation as the platform where people post violent videos linked to the conflict that they are unable to post on Facebook for fear of violating community standards. Two outlets mention that they have developed Apps but, while there is growing interest in Apps among Myanmar media, this is not where audiences tend to go for news and information.

The next chart looks at the languages used by the 40 outlets. All 40 publish in Burmese13 and 24 in English. Because they want the international community to know what is going on inside Myanmar, a larger number of outlets are publishing in English in the wake of the coup, although often just the main news stories, and for some infrequently. The language chart includes both Rohingya and Bengali languages; according to the two media in question, Bengali refers to the main language of Bangladesh.

Twenty-three of the 40 outlets interviewed say that since the coup they have continued operating with no interruptions; nine paused temporarily and later relaunched; one paused its operations, temporarily launched a different outlet, and then relaunched its original outlet; and four outlets permanently shut down and their staff later launched new outlets. Three of the media were launched post-coup.

Most of the 40 outlets surveyed for this report have changed locations since the coup. Thirty-five have now established their main operations in exile in countries bordering Myanmar, and one in a third country14. Only four have their operations inside the country: three in ethnic states under the control of ethnic armed organisations, and one in an area controlled by the military. Of the 35 outlets whose main operations are located in exile in neighbouring countries, six say they also have complementary cross-border operations15, and three describe their operations as multi-country 16. More than half of the outlets – 22 out of 40 – say they are in exile for the first time.

We have used the word exile for this report to refer to all of the outlets that currently have their main operations outside of Myanmar. Yet we are aware that it is a complex term, especially for the ethnic media that for decades have been operating in the borderlands of two countries, moving back and forth across the borders, and in some cases operating cross-border offices.

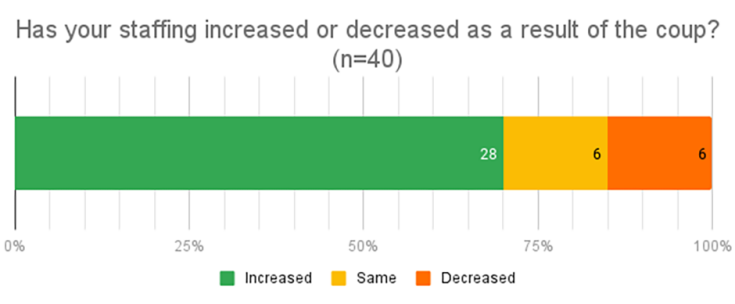

As the next two charts show, the 40 media outlets surveyed vary in size: two are large (70-150 staff), seven are medium-sized (25-69 staff), and 31 are small (1-25 staff). Twenty-five of the 40 senior media executives interviewed say they have increased the size of their staff since the coup, six have stayed the same, and six have decreased. The six outlets that say they cut their staff include 2 national and 3 ethnic outlets. The outlets that say they increased their staff include four national, four from the regions, and 14 ethnic media outlets. The three media outlets that were launched in the wake of the coup are also included in the ‘increased’ category.

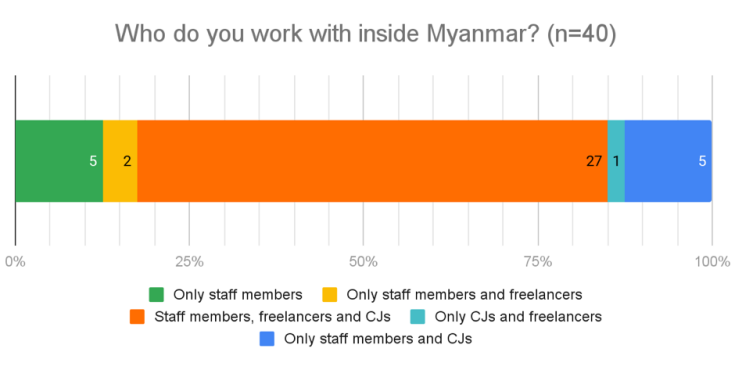

As the next chart shows, 39 of the 40 senior media executives interviewed say that they have staff members working inside Myanmar. The remaining senior media executive says they only work with freelance journalists and citizen journalists inside the country. A majority of senior media executives (27 of 40) say they also work with freelancers and citizen journalists inside the country. Twelve senior media executives say they either work with freelancers or citizen journalists inside in addition to their staff members.

For the next chart, the 40 senior media executives were asked to describe their outlets’ journalism in a few words. As you can see in the chart, only one described their journalism as somewhat independent, due to their struggles to do independent and impartial coverage of the resistance, as well as their post-coup dependence on donor funding. The other 39 used positive descriptors.

The senior executives seem keenly aware of the widespread criticism that much of Myanmar’s journalism has deteriorated in the wake of the coup, in terms of its independence and impartiality, particularly vis-à-vis the resistance. This is accompanied by a growing understanding that doing quality journalism protects an outlet’s brand, both in terms of developing loyal audiences, attracting donor funding and other opportunities, including being able to set up membership programs and subscription models, and monetising their digital platforms. Some say it is one of their biggest lessons learned since the coup.

Veteran media journalists and trainers say that some outlets have made great strides over the past three years in terms of their professionalism and ethical journalistic standards. But they caution there is still much to be done.

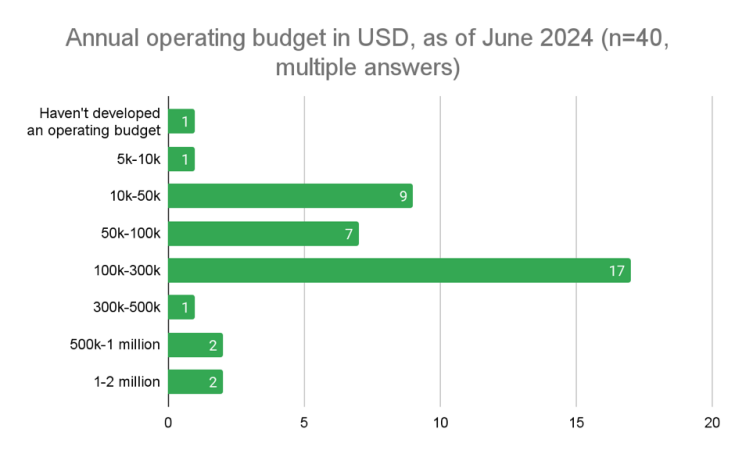

The final chart in this section presents the current annual operating budgets for the 40 media outlets that were surveyed. Seventeen say their annual budgets range from US$5,000 – US$100,000, another 17, US$100-300,000, and five from US$300,000-$2 million. One nascent outlet says they have yet to develop an annual operating budget.

The annual operating budget chart is a good jumping off point for the next section of the report that focuses on operating media businesses on social media.

Operating media businesses on social media

We should have focused more on the digital side of our operations before the coup, instead of focusing on print.

-Senior Myanmar media executive

The Myanmar senior media executives we interviewed in both 2022 and 2024 pointed to a similar realisation and lesson learned: that the coup had forced them to finally take the digital space seriously and that they wish they had embraced it sooner. This includes learning how to use tools to grow their audiences, digital security, digital monetisation skills and tools, and understanding digital analytics. With hindsight, some admit that they had had many opportunities to do this in the past, but did not fully embrace them or take them seriously enough. The space has become more complex in the post-coup environment due, among other things, to more stringent standards being applied by social media platforms, so they also acknowledge that they have had to face a very steep learning curve during a time of crisis to try to avoid being penalised by the platforms for violating these standards.

The 26 data charts in this section are divided into three areas: 1) digital audience growth since the coup; 2) digital revenue monetisation; and 3) an MDIF media partner case study. The section starts with an examination of digital audience growth.

The 40 senior media executives who were interviewed for this report say their outlets have experienced significant audience growth since the coup. The three media that launched new outlets in the wake of the coup, and therefore were starting from zero, experienced particularly strong initial growth.

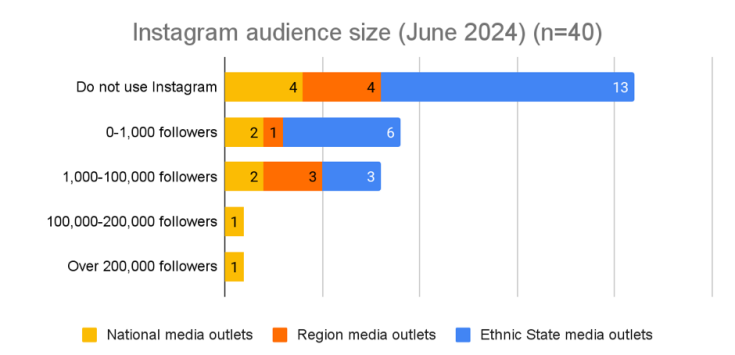

The 14 charts in this section examine digital audience growth since the coup. They cover: 1) Average Facebook, website, Youtube audience growth; 2) Average Facebook audience growth (followers); 3) Average Facebook audience engagement (monthly interactions); 4) Average YouTube subscriber growth; 5) Average YouTube monthly audience views; 6) Average website visitor growth; 7) Why do you think your digital audiences have increased?; 8) Have you invested in digital?; 9) Which news platforms have you begun using since the coup?; 10) Telegram audience growth (followers); 11) Telegram audience size; 12) TikTok audience size; 13) X (Twitter) audience size (followers); and 14) Instagram audience size.

The charts use percentages as a measurement. This is because percentages measure average growth, regardless of how big the outlets are, whereas real numbers measure total scale, and big outlets would therefore skew the reality.

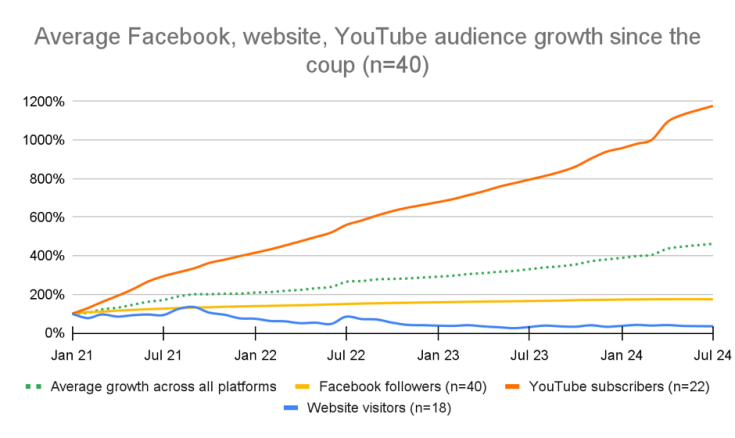

The first chart looks at average audience growth across all platforms, and then compares audience growth on each of the three Facebook, website, and Youtube platforms. As a measurement, the chart uses Facebook followers, YouTube subscribers and website visitors. It incorporates Facebook follower data for all 40 outlets, for 22 YouTube subscriber accounts, and for 18 website accounts.

As the chart below shows, it is the Youtube subscriber growth that stands out. There are a variety of reasons that help to explain this. More outlets have been focusing on YouTube content post-coup, in part because Facebook is illegal inside Myanmar but also because there is strong demand for video content by audiences wanting to not only read, but also see, what is happening around the country. As well, many media only had small YouTube audiences when the coup happened, so it is only post-coup that they have worked to develop them. As a result, the quality and quantity of YouTube content is increasing. Also, YouTube is legal inside Myanmar and does not require a Virtual Private Network (VPN), and this makes the platform faster to use. Although due to YouTube’s current policies they cannot monetise their audiences based inside Myanmar, they can still grow their audiences overall. There is also an opportunity to focus on growing diaspora audiences where monetisation is possible. The problems associated with Facebook’s decision to alter its algorithms twice in the three years since the coup, negatively impacting on the reach of news, have likely contributed to the growth in YouTube use. The fact that Myanmar audiences need to use VPNs to access Facebook, and now have to deal with the junta’s crackdown on VPNs have likely also contributed to this trend. The chart nonetheless shows a comparatively small, yet steady pattern of growth. For websites, on the other hand, visitor numbers are unstable and generally decreasing. There is one exception, however, based on our findings: if you do good quality journalism and build a loyal audience, they will be willing to go to your website to read the full stories.

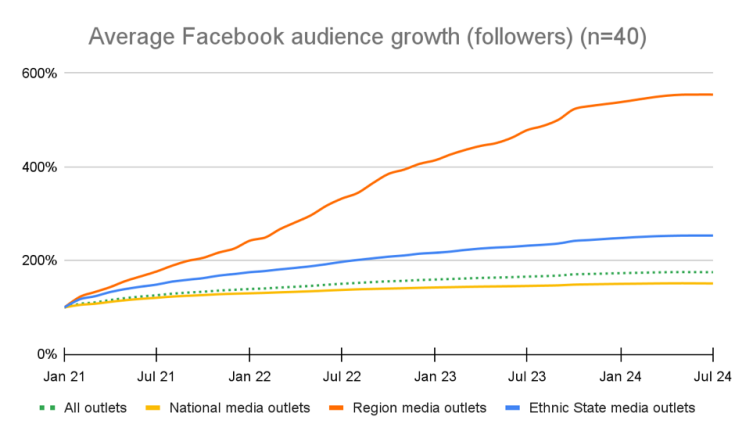

The next chart looks at average Facebook audience growth, and disaggregates the data according to national, region and ethnic outlets. As growing your followers is a well-established trend, it is unsurprising that the chart shows steady growth across all outlets, although of varying degrees. Follower growth is a common metric used by all media outlets; for example, it was used before the coup to attract advertising opportunities. Yet what it does not tell us is whether the outlets also have steady growth in terms of the people they actually reach. That information is in the Facebook audience engagement chart. What also stands out in this chart is that the follower growth for outlets from the regions looks very significant compared to ethnic or national outlets. There are several possible explanations: there are a smaller number of outlets from the regions that went underground after the coup, in some cases shutting down their outlets and then launching new ones with different names, which meant they had to completely rebuild their audiences. As is often the case, they therefore experienced initial rapid growth. The national and ethnic media are also growing, but as they were generally already well established they were continuing their steady growth rather than starting from zero. In addition, some of the big national outlets had already established large audiences before the coup.

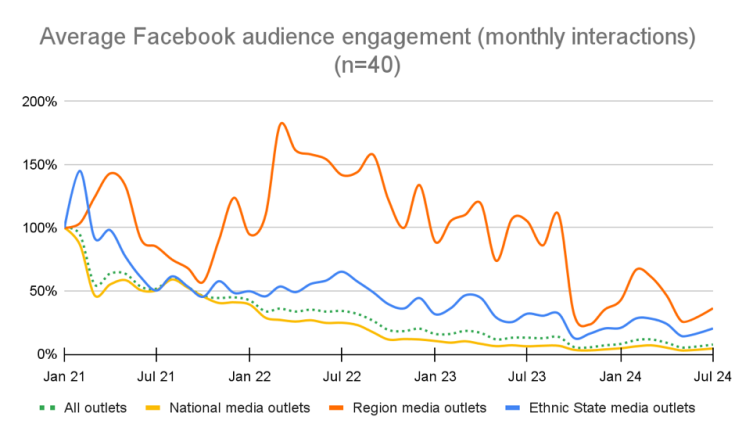

As the next average Facebook audience engagement chart indicates, engagement has been unsteady for all three media groups (national, region, ethnic), with a steady decline since early 2022, although with some comparatively small peaks in certain cases and for the outlets in the regions, a significant spike in 2022 and then an unsteady decline. This overall decline in reach mirrors the global trends after Facebook started changing its algorithm in July 2022, negatively impacting on the reach of independent news coverage.

The growth for media from the regions counters the overall trend, with a large peak in January 2022, followed by a steady decline, and many unsteady peaks. As well, in the immediate aftermath of the coup, the aggregated chart shows growth for ethnic media and a bit later for media from the regions, whereas the reach of national media declined. There are various potential explanations: ethnic media were better placed to react quickly to the coup, to seek safety, and to continue their coverage; they also had access to important information about what was happening in the ethnic states. Many of the outlets operating in the regions at first stayed put, with many going underground, so it took them longer to re-organise and to grow. There was also renewed interest in the regions due to the conflict that unexpectedly unfolded there. A minority of the national media outlets also increased their audience engagement right after the coup, but as this is aggregated data that growth is not captured in this chart.

The green line for all outlets tells the most important story, which is that the February 2021 Facebook block devastated the media, immediately cutting their actual audience reach by half. They have never fully recovered from this. We can also assume that the continuing decline may be linked to the military making it increasingly difficult to access Facebook. Yet despite the military’s Facebook block, there was an immediate bubble of audience interest in media content, which may be linked to an increased desire for information on the coup. But this bubble only lasted a month or so. After Facebook started changing its algorithm in the third quarter of 2022 there was a moderate decline in audience engagement, although nothing on the scale of the military’s block. The June 2024 data does not clearly point to an obvious impact from the VPN crackdown inside Myanmar. It may simply be too early to reach any reliable conclusion.

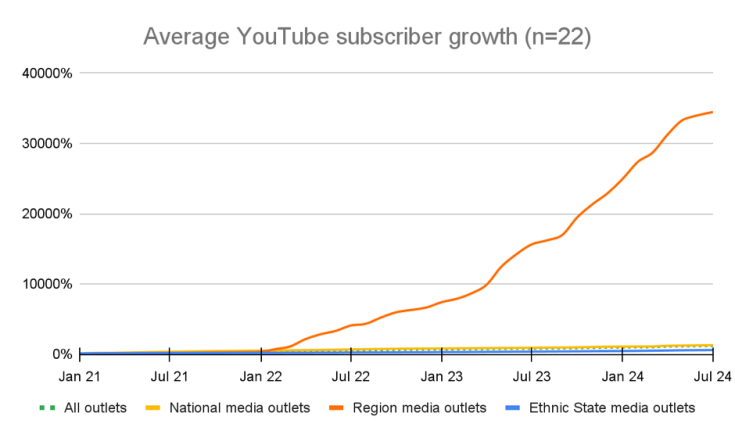

The next chart shows average YouTube subscriber growth. Given that the chart is using percentages as the measurement to capture all the trends, the dramatic growth of media from the regions is very visible, compared to the more muted growth for national and ethnic media. The reasons are similar to those explained for the previous charts. The 22 outlets in this chart comprise 4 national, 5 from the regions, and 13 from the ethnic states. To measure YouTube growth and audience views, we have multi-year comprehensive data for only 22 out of 37 of the interviewees who participated in the report survey. This is because three of the outlets do not have YouTube, and the 14 other outlets included in the survey are not MDIF partners and we do not therefore have access to their detailed data; one outlet had its YouTube channel hacked so has to start a new channel and there is as yet no subscriber data available.

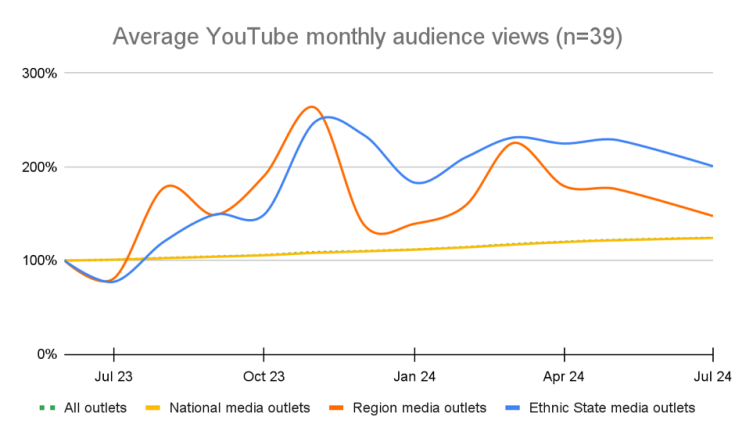

The next chart shows average YouTube monthly audience views. As data is only publicly available for the past year, the chart looks at the period from July 2023-July 2024. The available data indicates that all outlets increased views over this period. This coincides with many media increasing their focus on video production, potentially explaining the increase in views. (Please note that the All outlets line in the chart runs almost exactly parallel to that of national media.) There are only 39 media included in this chart as the remaining outlet does not have a YouTube channel.

The next chart looks at average website visitor growth for 18 outlets since the coup, including four national, five regional, and nine ethnic outlets. MDIF does not have data for websites managed by non-MDIF media partners, or else their websites are not functioning properly so there is no data available. It shows an average downward trend for all outlets. Ethnic outlets peaked in April 2021, soon after the coup, followed by smaller peaks. Growth for outlets from the regions plummeted after the coup, then went back up with various peaks and fluctuations, and then experienced a steep decline as of February 2024. National media peaked around August/September 2021, and then experienced a slow decline, with a smaller peak around July 2022. With very few exceptions, Myanmar media outlets do not tend to prioritise their websites, in great part because their audiences do not tend to go to websites for their news and information.

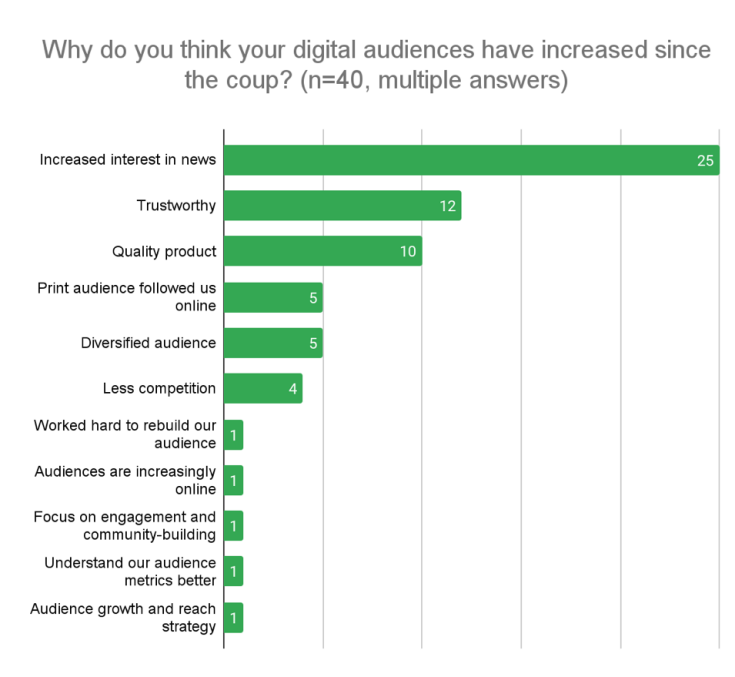

For the next chart, the 40 senior media executives were asked why they think their digital audiences have increased in numbers since the coup. The most common answer was an increased interest in news in the post-coup period.

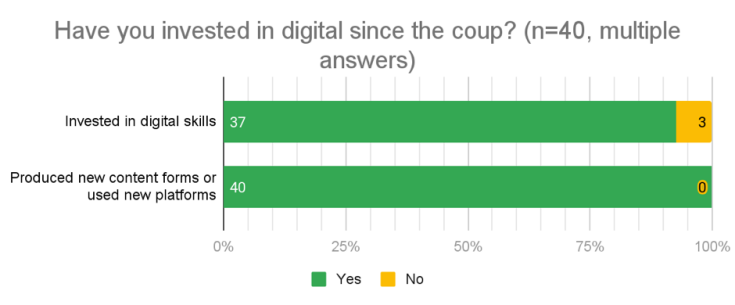

For the next chart the executives were asked if they had invested in digital since the coup. Thirty-seven out of 40 said they have invested in growing their team’s digital skills, and all 40 confirmed that they have adopted new platforms and new forms of content. The new forms of content cited include podcasts, video, audio, opinion pieces, features, essays, handbooks, newsletters, breaking news, in-depth stories, investigative reports, short text-only stories, interviews, and short-form stories.

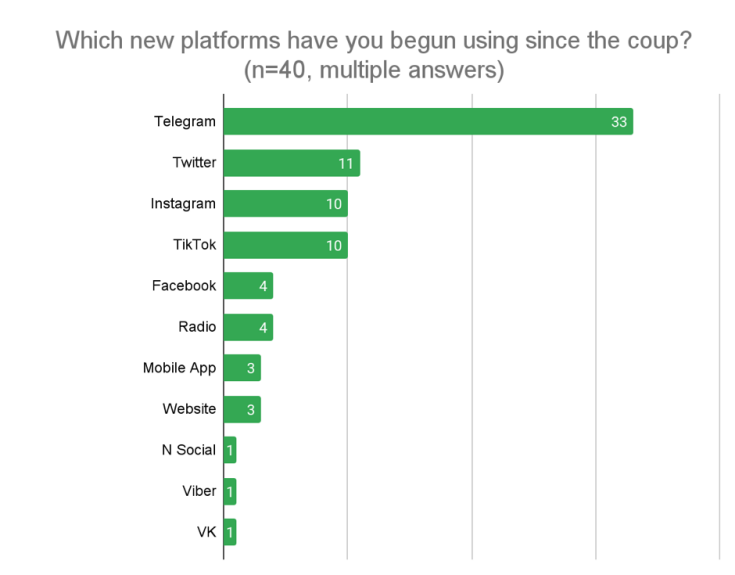

The next chart highlights the new platforms the outlets have adopted since the coup in an effort to grow and diversify their audience. Telegram is clearly the most popular new platform, followed by X, Instagram and TikTok. While the radio and TV categories include outlets that have established new stations since the coup, there is growing interest in broadcasting, especially radio, as a means to reach more remote audiences that have little to no internet access.

Emerging Platforms

We’re reaching new audiences through our new platforms and new forms of content.

-Senior Myanmar media executive

Telegram:

The next two charts look at Telegram audience growth (followers) and current audience size. As the first chart indicates, 33 of the 40 media outlets surveyed have joined Telegram since the coup. The other seven do not use this platform. Overall, national media have the strongest growth rate based on followers, followed by media from the regions and then media from the ethnic states. The growth rate for all outlets visibly picks up as of November 2023. Myanmar audiences are moving to this platform, as are local businesses to sell their products. The second chart indicates that national media and media from the regions have the most followers.

Overall, it is fair to say that Telegram use among Myanmar media is growing, due to the challenges linked to Facebook and YouTube, but is not yet an important platform. Based on our interviews and additional research, some of the Telegram accounts are not very active and in some of the cases where the accounts are active, they do not have significant audiences, and five ethnic media outlets and two national outlets do not have Telegram accounts.

Tiktok:

Myanmar media outlets express more interest in TikTok than they did before the coup and in the early period after the coup, in part because they considered it to be more focused on entertainment. Now, though, the media see the platform as a way to diversify their audiences and attract younger ones; one advantage is that the TikTok algorithm enables outlets to grow their audiences more quickly than on Facebook. Some senior media executives also say they hope to counter the devastatingly high levels of misinformation and disinformation on TikTok by providing verified news and information. At the moment, 10 of the 40 outlets surveyed are on TIkTok, although once again this does not mean that they have high levels of engagement. Of the 10, five are from the ethnic states, three are from the regions, and two are national.

X:

The next chart looks at X audience growth, based on followers. Twenty-five of the 40 outlets surveyed have X accounts, yet say they are not the main way they engage their audiences and that they are not very active. Most of the accounts are in English; it is possible to write in Burmese, but only a small minority choose to do so. Based on the chart, the national media outlets have experienced the greatest growth, followed by the outlets in the regions, and then outlets in the ethnic states.

Instagram:

The next chart looks at current Instagram audience size. Nineteen of the 40 outlets surveyed have Instagram accounts, once again in an effort to grow and diversify their audiences, including younger generations; athough again, most are not very active. One area where the outlets could quite easily strengthen their engagement is by cross-posting their Facebook Reel videos. Nine of the ethnic outlets have Instagram accounts, six of the accounts are national, and the remaining four accounts were established by outlets from the regions.

Post-coup revenue development

Before the coup, we didn’t really think about money. But since the coup we’ve realised that if we want to run a professional operation we need support.

-Senior Myanmar media executive

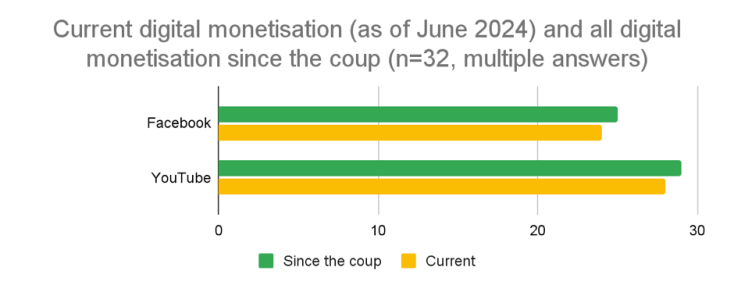

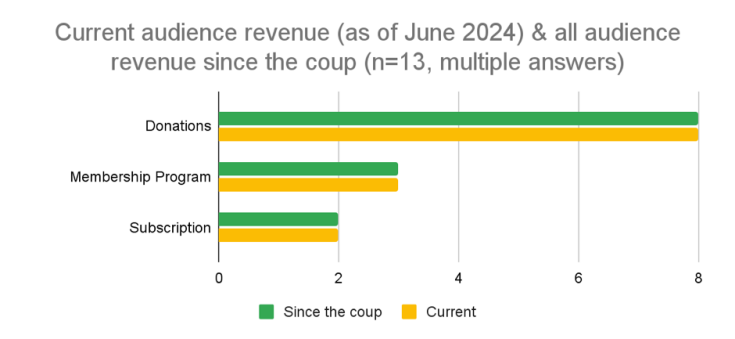

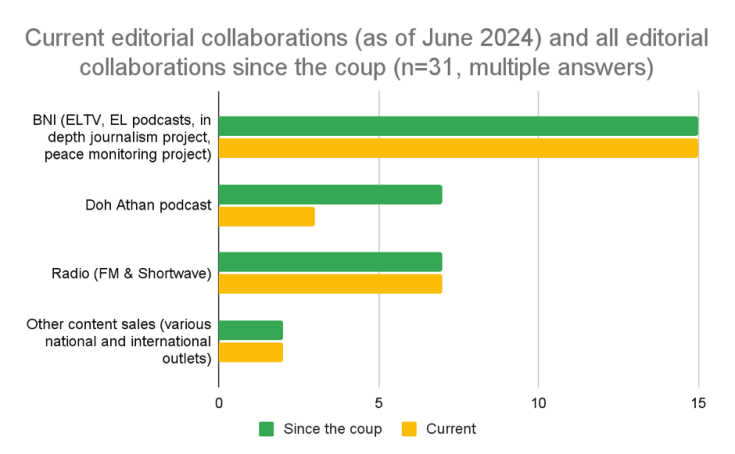

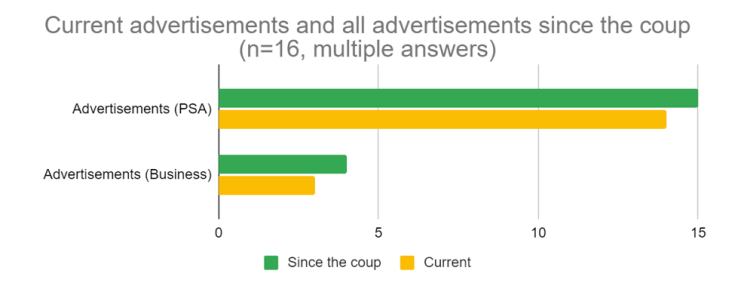

This section looks at post-coup revenue development. The charts cover: Current digital monetisation and all digital monetisation since the coup (Facebook & YouTube); current audience-linked revenue and all audience-linked revenue since the coup; current editorial collaborations and all editorial collaborations since the coup; and current ads (PSAs and business) and all ads since the coup.

Donor funding

Almost all of the 40 senior media executives interviewed say they continue to depend on grants, either partially or totally. Thirty-nine out of 40 say they have received some form of grant since the coup. Thirty-three also say they have at least one current grant; 19 of the 33 add, however, that their current grant is small and short-term. The executives say that international funding opportunities started decreasing in 2023, and that 2024 has proven to be extremely challenging; this is in large part due to the significant periods between one grant ending and a new one beginning, and uncertainty as to which outlets will receive new grants. Another challenge is that available funds are mostly short-term and one-off, and often tied to content production. The executives say that what is most needed are long-term, unrestricted funds to cover their core operational costs.

Revenues

Prior to the coup, many media were unable to access digital revenue opportunities on Facebook and YouTube, largely because they had not sufficiently invested in digital and therefore did not have a strong digital focus or enough audience subscribers, followers, and traffic to become eligible for social media monetisation. Yet as illustrated in the digital audience growth section of this report, those circumstances quickly changed in the wake of the coup, with most private media experiencing dramatic digital audience growth which in turn made them eligible for monetisation.

The next chart shows the number of outlets monetising their Facebook and YouTube platforms currently, as well as since the coup. For both platforms the chart indicates a small drop in the number of outlets monetising their digital platforms currently. There may be several reasons for this. On Facebook, for example, monetisation is often suspended because of community standards violations related to the nature of conflict news, which frequently depicts violence, and copyright issues, such as using the same footage shared by citizen journalists across multiple outlets. As well, one of the outlets surveyed lost their ability to monetise their YouTube channel after it was hacked; they are currently working on setting up a new YouTube channel. The fact that Facebook shut down Instant Articles in April 2023 may also have contributed to the slight decline.

The next chart looks at audience revenue, namely donations, membership programs, and subscriptions. For this particular chart, the comparative data is the same for both categories (currently and since the coup). Although these revenue streams were growing in popularity in Southeast Asia and elsewhere in the world, there was very little focus by Myanmar media on generating revenue from audiences before the coup. Interest in them has increased over the past three years since the coup, although not all outlets currently fulfil the main requirements to successfully generate audience revenues. Of the 13 outlets included in the chart, for donations, six are ethnic and two are national; for subscriptions, one is national and one is from the regions; and for membership programs, one is national and two are ethnic. One of the membership programs was established before the coup by Frontier Myanmar and it has proven resilient even in the face of a coup, with revenues from this currently covering approximately 50% of its operating costs. Myanmar Now set up a subscription service in 2023 that is steadily growing. Its decision to only monetise its English language site reflects its core value of ensuring that Myanmar people have access to important news, information, and investigations in the country’s main language.

The next chart looks at editorial collaborations currently and since the coup. The data for the two categories is also similar (currently and since the coup); the only exception is Doh Athan which currently has fewer partners.

The next chart looks at current advertisements and all advertisements since the coup. It is divided into two categories: PSAs and business advertisements. PSA growth since the coup has been an unexpected opportunity. Since 2020, PSAs have been a central part of MDIF’s Sida-funded business coaching program. Since September 2021 MDIF has been reaching out to other organisations to help its partners expand and diversify their PSA clientele. Building upon this base, some of its partners have now established their own PSA clients. One of the reasons PSAs are so popular post-coup is that they enable organisations to reach Myanmar people with their public service messages even when they cannot physically work inside the country. The second category – advertisements from small businesses – is also growing since the coup, albeit from a very low base, and primarily in areas that are not under control of the Myanmar junta.

13 Although Frontier publishes almost exclusively in English, it also publishes the Burmese-language podcast Doh Athan.

14 In this context, third countries refer to countries that do not border Myanmar.

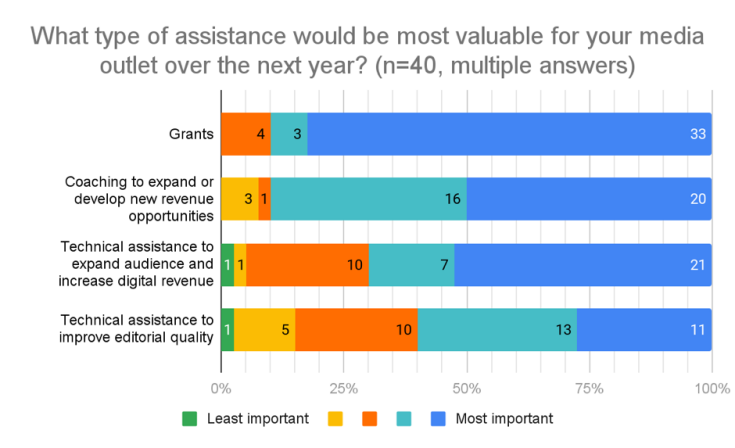

15 In this context, cross-border refers to media outlets that maintain some form of operations on two sides of a border. Some ethnic media have historically maintained cross-border offices in Myanmar and Thailand and/or India.