A Media Development Investment Fund Report

People trust and depend on independent media much more than they did before the coup.

Senior Myanmar media executive

Preface

On 28 June 2018, a gunman entered the newsroom of Capital Gazette and killed five staff. Capital Gazette is a newspaper that serves the city of Annapolis, Maryland in the United States. Despite the brutal attack, the staff at Capital Gazette decided to continue working to get the next day’s edition out.

At the end of the year, Time Magazine honoured Capital Gazette as Person of the Year, together with Reuter’s Myanmar investigative journalists Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, Filipino journalist and 2021 Nobel Peace Prize laureate Maria Ressa, and Saudi exiled journalist Jamal Kashoggi who had been brutally assassinated in the Saudi Embassy in Turkey.

For its cover, Time Magazine chose the words: The Guardians and the War on Truth.

The Guardians and the War on Truth continue in today’s world, including in Myanmar. If Time Magazine still considers journalistic watchdogs for its person of the year award, then all Myanmar newsrooms deserve the title in 2022.

On 31 January 2021 I went to bed at 11pm knowing that something horrible would happen the next day. Journalists in Nay Pyi Daw, the capital of Myanmar, were speculating that a military coup was under way. A few hours earlier, I wrote an op-ed for a local daily newspaper telling military leaders that a coup was not an option and that if they carried through with it the country would be doomed.

At 4:30am someone telephoned me and said, “Wake up sir, the military is staging a coup”.

The day I was bitterly anticipating had finally arrived. I opened the window of my bedroom and looked out into the darkness outside. I realised that this was the second time I had experienced a military coup in my lifetime, and that it had been 33 years since the 1988 failed revolution.

I asked myself how the new generation of journalistic watchdogs would respond to this tragedy. Do they have enough strength and courage?

The next morning, when the papers appeared on the streets, I saw my article and knew that it was too late.

Over the next few months, we witnessed mass protests in cities, towns and villages across Myanmar. The movements were bigger than the 1988 uprising that I had experienced as a young leader of a student union in central Myanmar. Another big difference was the new generation of journalists who were bravely covering the aftermath of the coup. We did not have that in 1988.

Seeing the work of young journalists during this political turmoil, I have whispered to myself that the genie has been let out and is not going back into the bottle.

For me, the journalism sector’s response to the coup has clearly demonstrated that the international community’s several decades of support for independent media in Myanmar has been very meaningful.

But military leaders have responded harshly to our journalists’ work. Many journalists have flooded into neighbouring countries. Others have been imprisoned. Yet wherever they are, if they are able, they are continuing to report and to tell Myanmar people the truth.

When people in Myanmar wake up every morning, they look at their mobile phones and see the news stories of the day produced by these brave journalists. And they try to believe that hope is still in Pandora’s box.

Without independent media, the people of Myanmar will not survive morally.

Thit Ywet, Columnist, Yangon

Introduction

The Business of Independent Media in Post-Coup Myanmar examines the ways in which independent media businesses have responded to, and been changed by, the 1 February 2021 military coup.

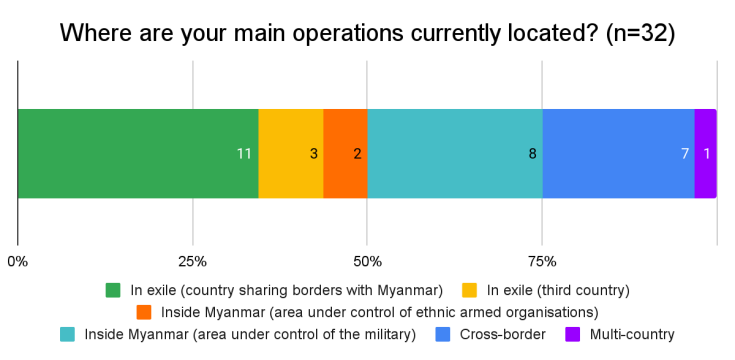

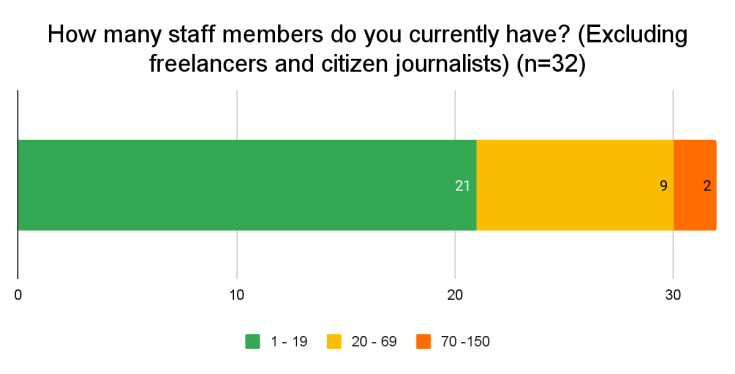

For this report, MDIF conducted survey interviews with senior executives of 32 independent media outlets. Together, they represent eight national media, 19 local media from seven ethnic states, and 5 local media from four regions.1 Their operations vary in size: two are large (70-150 staff), nine are medium-sized (20-69 staff), and 21 are small (1-19 staff). Four of the outlets were launched in the wake of the coup; 16 were launched during the decade-long ‘political opening’ from 2011-2021; and another 12 were launched during previous military regimes. Since the coup all but one have moved their main operations to a new location outside the control of the Myanmar military junta or else have gone underground inside the country. Eight are now located inside Myanmar in military-controlled areas, two are in parts of the country controlled by ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), seven have cross-border2 operations, 11 are in exile in countries bordering Myanmar, three are in exile in third countries, and one has multi-country operations. The only outlet that is still operating openly in its original location in an area controlled by the military is no longer publishing political content.

While not representative of all independent media outlets, this report offers insight into a broad cross-section of the post-coup independent media world, including with regards to audiences and commercial3 revenue challenges, opportunities, lessons learned, and future priorities. To complement this data, and to provide nuance and context, four Myanmar media leaders share their experiences and reflections in personal essays, and an MDIF media business coach recounts his post-coup audience development and monetization work with an ethnic media outlet. The ‘Operating media businesses on social media’ section provides comparative data, as well as insights into the complex business relationship between Myanmar media and the social media platforms on which they publish their content. The report starts with a summary of key findings and lessons learned.

1 Regional media outlets function primarily to serve the information needs of a particular geographic area in Myammar’s seven regions; a large percentage of the population in these regions is composed of the majority Bamar ethnic group. Ethnic media outlets function primarily to serve the information needs of a particular ethnic minority nationality, including, but not limited to, the ethnic populations residing in Myanmar’s seven ethnic states.

2 In this context, cross-border refers to media outlets that maintain operations on two sides of a border. Some ethnic media have historically maintained cross-border offices in Myanmar and Thailand and/or India.

3 In this report, commercial and/or business revenue refers to all non-grant income.

Key findings

Because of the coup our digital audiences have skyrocketed, especially among the younger generation and people from outside our traditional coverage area.

Senior Myanmar media executive

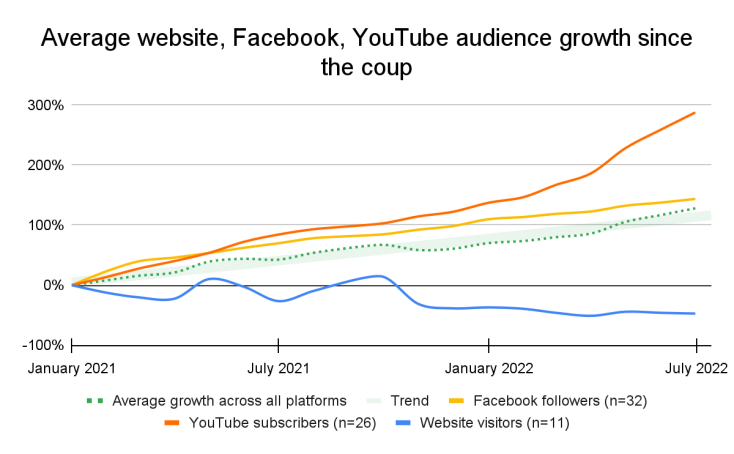

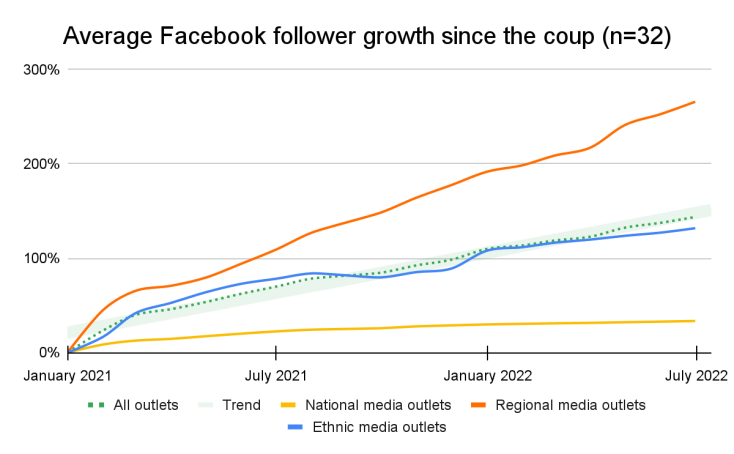

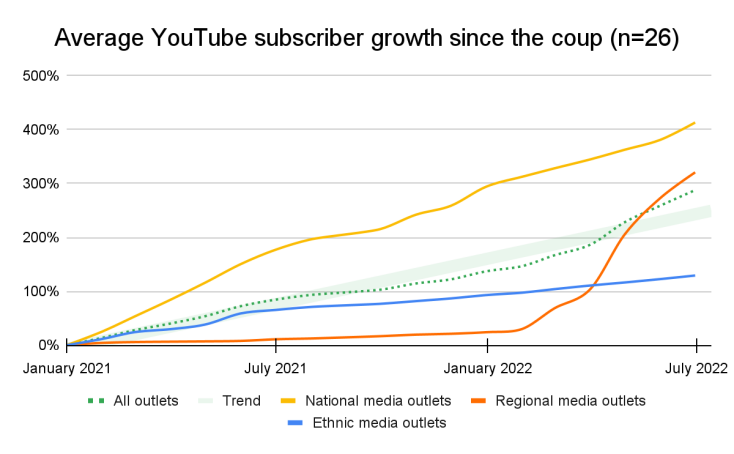

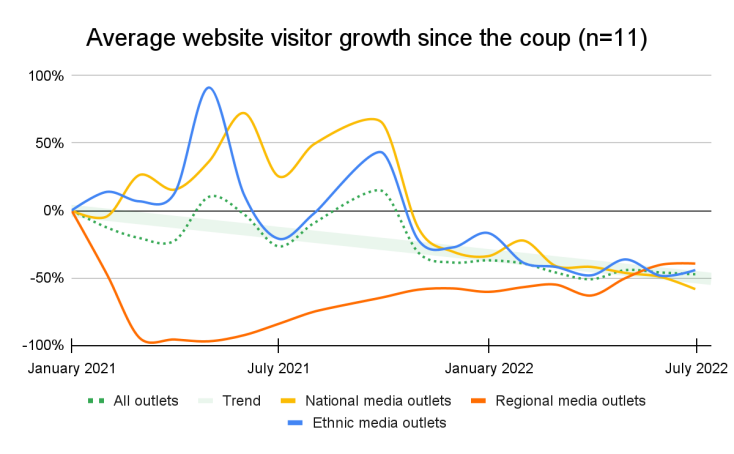

Audience growth: All 32 senior media executives interviewed for this report confirm significant audience growth since the coup. Given that they were starting at zero, the four new outlets that were launched in the wake of the coup experienced particularly strong initial growth. Aggregated audience data for the 32 outlets indicates an impressive 128% average growth across all platforms. When the data is disaggregated, though, the numbers are even more notable. Average YouTube subscriber growth, for example, is 288%, and average Facebook follower growth, 144%. It is the websites, with an average negative growth of -47%, that pull the overall average down across all platforms.

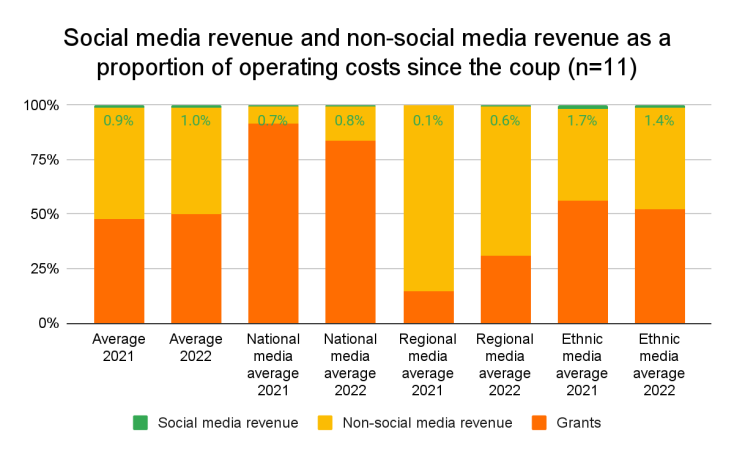

Commercial revenue: 30 of the 32 senior media executives interviewed say they have lost most, if not all, of their traditional commercial revenues (advertising, print sales) as a result of the coup. One of the other media executives launched their first outlet nine months after the coup so is not included; the other media executive has a membership program that grew significantly in the wake of the coup so was not affected. To serve as a more detailed commercial revenue case study, we have aggregated data from 11 diverse media outlets (national/ethnic/regional) that participate in MDIF’s intensive one-on-one media business coaching program; the data covers 2021 and 2022, and includes projections until the end of 2022. Based on the aggregated data, non-social media commercial revenue, including content sales, membership programs, donations, and public service announcements (PSAs), covers an average of 52% of the outlets’ operating costs in 2021, and 49% in 2022. Social media commercial revenues, on the other hand, are negligible, at 0.9% in 2021 and 1% in 2022. Grants cover the revenue shortfall for both years: 47.1% for 2021 and 50% for 2022. When the data is disaggregated, however, significant variations emerge depending on the media type. For national media, for example, 8% of operating costs are covered by non-social media revenues in 2021 and 16% in 2022. Once again, these social media revenues for national media are negligible at 0.7% in 2021 and 0.8% in 2022. Grants play a very significant role in making up the revenue shortfall for both years for national media: 91.3% for 2021 and 83.2% for 2022. For ethnic media, an average 42% of operating costs are covered by non-social media revenue in 2021 and 46% in 2022; ethnic media’s social media revenues are also higher than national media’s at 1.7% in 2021 and 1.4% in 2022. Grants cover the revenue shortfall for both years for ethnic media: 56.3% for 2021 and 52.6% for 2022. For regional media, 85% of operating costs are covered by non-social media revenues in 2021 and 68% in 2022; social media revenues are again negligible at 0.1% in 2021 and 0.6% in 2022. Once again, grants cover the revenue shortfall for regional; media: 14.9% in 2021 and 31.4% in 2022.

Social media monetization: 23 of the 32 media executives interviewed say they have been earning revenues on their social media platforms post-coup, albeit on a very minimal scale. This is largely the result of their significant audience growth over the past 20 months. The majority of these outlets only started accessing digital platform monetization in the wake of the coup. Previously their audiences were not large enough to allow them to access monetization and, in some cases, they also did not have sufficent knowledge or skills to do so.

Print media: Nine of the 32 senior media executives interviewed had print media operations before the coup. Eight say they had to shut down their print media after the coup was carried out. For most of them this happened in March and April 2021, and meant their major sources of revenue – print sales and advertising – was lost. Only one media outlet – a small ethnic operation – is still continuing to print and to distribute a small number of copies of its publication. One of the senior media executives interviewed noted that it was an extremely difficult decision to shut down their print media, and that they still miss it and hope one day to relaunch it.

Donor funding: 31 of the 32 senior media executives interviewed say their donor funding has increased, in some cases significantly, in the wake of the coup. The other media executive launched their first outlet nine months after the coup so their data is not included. As noted above, aggregated data compiled by MDIF from the 11 media participating in its intensive one-on-one media business coaching program shows that grants cover an average of 47% of the outlets’ operating costs in 2021, and 50% in 2022. When the data is disaggregated, however, significant variations again emerge depending on the media type; for national media, grants cover 91.3% of operating costs for 2021 and 83.2% for 2022 ; for ethnic media, 56.3% of operating costs for 2021 and 52.6% for 2022; and for regional media, 14.9% in 2021 and 31.4% in 2022. These calculations include projections until the end of 2022.

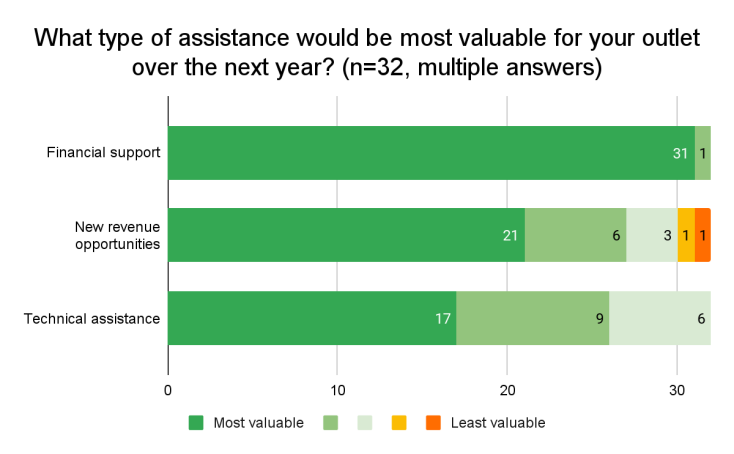

Looking ahead: Only one of the 32 senior media executives interviewed says they are planning to shut their outlet due to financial concerns. The other 31 executives are unanimous in saying they will not give up and that they are already planning for the longer term. When looking ahead over the next year, almost all the executives say that financial support would be the most valuable assistance they could receive, followed by new revenue opportunities, and complementary technical assistance.

Lessons Learned

People turn to credible, independent media they can trust for news and information during a crisis.

Senior Myanmar media executive

Adopt digital: The importance of prioritizing digital is the most frequently cited lesson learned by the 32 senior media executives interviewed, in some cases accompanied by regret that they had not taken their digital platforms, content, and skills development seriously enough prior to the coup. Prioritizing digital was also the most frequently cited lesson learned by the 34 senior media executives interviewed for MDIF’s January 2021 COVID-19’s impact on media operations in Myanmar report. The military coup has arguably had an even stronger impact than the pandemic with regards to digital disruption, forcing media outlets to quickly improve their digital capacity, resulting in an increase in the quantity and variety of both their content and platform use, as well as strengthened digital skills and knowledge.

Rethink business plans: In the wake of the coup, survey respondents lost most, if not all, of their traditional revenue sources and, as a result, had to quickly become creative and to start working on new business plans and alternative revenue opportunities. Many of the senior executives interviewed cite the desire, and need, to build new business collaborations, including content sales and CSO and media partnerships, as well as to experiment with membership programs. While appreciating the support they are getting from donors, many also say they regret their newfound dependency on grants; one of the interviewees adds that they are doing everything they can to avoid accepting grants as that, they say, makes media outlets lazy.

Protect your media business on social media platforms: While it is vital for platform owners like Meta (Facebook) and Google (YouTube) to address misinformation and disinformation, and to protect their editorial standards, they must do so without harming legitimate content producers, including the 32 outlets interviewed for this report. As current platform policies are hampering independent media outlets’ ability to monetize their content, it is urgent that sustainable solutions be identified. More details about this are in the ‘Operating media businesses on social media’ section of this report.

Stay safe: That safety and security have to come first is a vital lesson cited by many of the media executives interviewed for this report. As a result, their top priority is to do whatever they can to protect their staff, and to train them so that they can protect themselves, especially those working on the ground.

Be prepared: Even more than the dramatic impact of the pandemic, the media executives interviewed say that the sudden, bloody military coup has driven home the need to always be prepared when working in unstable environments with a long history of conflict. They add that the coup has strengthened their respect for, and understanding of, strategic planning and risk assessment, and the need to remain flexible and nimble so as to ensure rapid response when crises happen.

Do trustworthy journalism: Much like the pandemic, the coup has been a clear reminder of the value of high quality journalism, as a means to grow audiences and to inform and educate them during crises, as well as to attract financial support, be that via donations or donors. One of the executives adds that this is also a strong reminder to stick to professional journalism, and to not engage in activism.

Instil good management practices: As a result of the coup, a number of the media executives say that they have learned the tough lesson that they cannot survive a crisis without establishing good management practices.

Work cross-border: In the wake of the coup, the media that were already working cross-border have proven to be among the most nimble and safe due to the strong networks, resources and teams they had already established in neighbouring countries.

Take care of your staff: A number of media executives observed that as a result of the coup they have learned they can trust, and depend on, their staff, and that the crisis has made their teams stronger. Some also emphasized that the coup has taught them the importance of making way for younger staff members’ new and creative ideas, as well as their digital knowledge and savvy.

Build strong networks: The outlets that were already part of strong networks have found it easier to set up their operations in exile. One of the senior media executives who is working for the first time in exile says that this is an important lesson learned, and that it would have been easier if they had engaged more actively in networking in the pre-coup period.

Respect local media: Local media from Myanmar’s ethnic states and regions have proven to be valuable resources for both national media and their media peers in other regions and states in the post-coup period. Ethnic media in particular have drawn upon their long experience with conflict to help increase national media’s understanding of their country and to strengthen their post-coup coverage. Some ethnic media have also helped to protect their non-ethnic media colleagues by facilitating their access to the border areas that are controlled by ethnic armed organizations.

In the following essay, a senior media executive reflects on what he and his team have learned from closing their outlet inside the country and then relaunching it in exile.

Rebuilding in exile

At first we thought we could survive inside. But then some of our reporters were detained and the rest of us had to hide. Authorities also revoked our media licence, so sources were scared to speak to us. I sent half of our team into our country’s border areas where ethnic armed organizations would protect them from the military. But even there, due to the crisis, they didn’t have the kind of freedom of expression we were used to, or access to the kind of information we needed. When our detained reporters were finally released the decision became clear – we had to move across the border into Thailand. I had a serious discussion with my team and said they could make their own decision about their future. Half of them decided to move. The other half decided to stay put, and most of them stopped working with us. When we were inside we had 31 staff. Now we have 15.

I lived in exile in Thailand during the last military regime and then returned to Myanmar to set up an independent media outlet in the ethnic state where I was born and grew up. I’m used to conflict, abuse and oppression. That’s the sad reality when you live in the ethnic states where the Myanmar military has waged a longstanding battle against ethnic armed organizations and the ethnic nationality populations who live there.

It was my dream to set up a media business, but the reality was tough, trying to drum up enough revenue to support ourselves through local advertising, journal sales and other creative means. Just before the coup we were covering close to half of our operating costs. It was really hard work, but we had a strong team of dedicated journalists and we were living good lives surrounded by our families.

Our team has now been in Thailand for eight months. We know we’ve made the right decision for our future and the future of our country, and we’re grateful we can still do our jobs. We’re also grateful that we have proper visas. But we’re making a lot of sacrifices, and we worry a lot. We’re not in our own country anymore. Our families are still inside. We’ve lost many of our support networks. We can’t register here as a media organization, and we can’t let our Thai friends know we’re journalists. Some of our reporters don’t even want to show their faces anymore so they can’t do tv programs. We also don’t know how long our visas will carry on, and how we’ll renew our Burmese passports when they run out. Most of the team has never lived outside of Myanmar before so there are also cultural and language barriers. Luckily, though, I know the country and the language, so I can translate, and also help when they need health care. I’ve tried to reassure my team that they’re not alone. I’m their brother and their father. Many of our ethnic media friends are also here.

After the military revoked our licence, we shut our outlet down for 10 months. We were worried we’d lose all of our audience, but since relaunching a lot of them have come back. That means we didn’t have to start all over again from zero. But so much else has changed. We can only do phone interviews and our communication costs have skyrocketed. Calling from an international number also scares our sources. We now live together in a compound and cook all our food together to save money. We can only afford to pay Burmese level salaries so we cover our team’s accommodation, food, electricity and communications. At one point I was so worried about health care costs that I bought exercise equipment for the staff and started waking them up very early in the morning to go trekking.

Sometimes I wonder why I’m doing this instead of going back home and setting up a different kind of business. But I don’t want to be selfish.

Our goal inside Myanmar was to become a self-sustaining media business. We didn’t want to feel like parasites, dependent on international funding. But now we’ve lost most of our revenue and we had to leave everything behind. We need multi-year core funding, health insurance and mental health support, so we can stop worrying. Without that, everything will fall apart.

We don’t think about the future anymore. Everything is unclear.

Ko Paul, Senior Myanmar media executive

The post-coup independent media world

At the annual Dili Dialogue Forum, held in August 2022 in the Timor Leste capital, a writer from the junta-sanctioned Myanmar Press Council named Aye Chan did a presentation which, in his words, was meant to set people straight about the distorted reporting and fake news by Myanmar’s private, independent media.

As analyst David Mathieson observed in a subsequent Myanmar Now op-ed, “Particularly unsettling within the context of a media conference, he attacked Myanmar’s news sector writ large, claiming without evidence of any kind that media had “become a tool for terrorists,” with “20% of donations collected by them going to media for writing fake news on FB [Facebook].” Conference delegates were caught completely off guard by the junta-driven presentation, Myanmar media protested, and the Timor Leste press council released a public apology.

The Myanmar Now op-ed ran on 9 September. One week later, on 16 September, Myanmar journalist Htet Htet Khine, a freelance producer for BBC Media Action, was sentenced to three years in prison with hard labour on trumped up incitement charges under Section 505a of the Penal Code, which criminalizes incitement and the dissemination of false news.4 The sentencing took place more than one year after her detention. On the same day, Frontier Myanmar journalist Ye Mon published a distressing first hand account of being beaten and raped by regime soldiers in December 2021 after being detained at Yangon International Airport.

All of these stories illustrate the relentless efforts of the junta to discredit Myanmar’s independent media actors, and to crush them using any and all means at their disposal.

On 31 January 2021 – the day before the military coup – MDIF published a report entitled COVID-19’s impact on media operations in Myanmar. Today it serves as a stark reminder that at the time of the coup independent media businesses were already facing crippling challenges. One clear example is that half of the 34 survey respondents at that time reported a more than 75% drop in income as a result of the pandemic, significantly greater than the 40-60% decline being experienced by media companies MDIF was working with elsewhere around the world.

As part of that survey, senior media executives were asked what they thought their media operations would look like as of mid-2021. From the vantage point of the subsequent coup, it is poignant to read their answers. Thirty-two of the 34 predicted their operations would survive, and of those, 25 said they would not look the same. Ten said they would be stronger, five, that they would be larger, and five more, that they would be digital-only operations. Three said their products would be different and in some cases no longer produced. Two others said they were unable to make a prediction in such uncertain times – wise words indeed, as the day after MDIF published the report everything changed.

Since the coup, more than 140 journalists have been detained, 57 journalists remain in detention, 12 independent media have had their publishing licences revoked, and four journalists have been killed. The vast majority of non-state owned media outlets have gone underground, moved to border areas, or into exile. Commercial advertising income, often these outlets’ largest source of revenue previously, has almost totally dried up, and they have had to rethink the business side of their operations. As if that were not challenging enough, since it is too dangerous for journalists to cover stories on the ground, they have also had to reinvent the way they do journalism.

In the wake of the coup, the military junta was also quick to impose restrictions as it sought to control the digital narrative. Short internet outages were replaced with months-long shutdowns – which have continued until now in parts of the country where military operations are taking place – and then by whitelisting, when junta officials only allow access to approved websites and platforms that are on a ‘whitelist’.5 That ‘whitelist’ does not include the media outlets interviewed for this report. Telecommunications operators were ordered to implement surveillance without any safeguards, which prompted Telenor, a Norwegian multinational telecommunications company, to sell its Myanmar operations. Qatari telecoms operator, Ooredoo, has more recently also decided to do the same. Yet, despite the digital crackdown, internet penetration has continued to grow, with 7% more people accessing the web in 2022 compared to 2021.6 Three-quarters of people with internet access are also reportedly using Facebook.7 At the same time, many users have improved their digital security skills to protect themselves and to protect each other. This includes using Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) – the safest way to hide digital identities and access blocked sites such as Facebook – and making sure their phones are wiped clean to ensure the miltary cannot access sensitive data if they are stopped and their equipment checked. According to Free Expression Myanmar (FEM) advisor Oliver Spencer, Myanmar’s digital future is closely linked to the military’s strategy for control over civic space: the military has repeatedly implemented shutdowns, invested in a whitelisting approach to the internet, including blocking Facebook, and eroded digital rights by amending laws. According to Freedom House’s Freedom on the Net 2022 report, Myanmar, Russia, Sudan and Libya have had the steepest declines in interent freedom in the world.

4 On 27 September Htet Htet Khe was sentenced to a second three year prison term. (https://cpj.org/2022/09/myanmar-sentences-journalist-htet-htet-khine-to-second-3-year-prison-term/)

5 https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/whitelisted-internet-takes-myanmar-back-to-a-dark-age/

6 https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-myanmar

7 https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-myanmar

Advertising, influencers, and the coup

In the immediate wake of the coup Myanmar’s media advertising sector went silent, especially in February and March 2021. Companies were advised to stay quiet, to stop their business campaigns, to not attract attention for fear of being viewed as either pro- or anti-military, and to avoid the negative consequences that might follow.

By late April, advertisers and agencies began exploring the possibility of starting up again on a more modest scale, but they encountered myriad challenges. One of the most important was linked to the long-established use of celebrities and social influencers to sell advertisements. Many of the highest profile and most influential celebrities and social media influencers were in prison for supporting, and participating in, the anti-coup movement. Some businesses had videos of them that they had shot before the coup, but they risked being detained and imprisoned if they used them. Advertisers also had to avoid the celebrities and social influencers who had not been charged or imprisoned as the Myanmar public were wary of them, suspecting that if they were free they must support the military. Even media outlets producing military-aligned content were problematic for advertisers: the public was doubtful about the reliability of their content and questioned why they were able to continue operating when other media were facing such difficulties, and this also made advertisers hesitant. Even the advertising for the military’s long-standing powerful broadcast business partners was said to be affected.

By the end of July 2021, six months after the coup, the advertising sector was very slowly starting to regain momentum, although agencies and businesses continued to lose money, and the economic forecast remained bleak. The hope was for the sector to at least eventually break even, but the coup and the COVID-19 pandemic were continuing to deal a huge double blow.

Print media businesses in particular had already been facing financial problems in 2020 as a result of the pandemic when distribution, always challenging, became even more problematic. But then came the coup, and most were quickly obliged to shut down.

By October 2021, Myanmar’s local currency crisis and US$ shortage had driven up the cost of imports and exacerbated the country’s economic challenges. The value of the local currency, the kyat, fell about 50% after the coup. Myanmar’s foreign reserves held in the U.S were frozen, and multilateral aid suspended. Restrictions on cash withdrawals inside the country also raised concerns about keeping money in local banks and this resulted in people turning to more secure foreign currencies.

Despite these crippling issues, during the first half of 2022 the advertising sector started showing renewed signs of life. Spending was up, albeit almost entirely reserved for crony television companies like Skynet, Forever Group, and Fortune. Some high profile social influencers were released from prison, yet if they failed to speak out against the coup, they lost public support; with no other options available, advertisers started featuring less high profile travel bloggers or, in their words, C-rated influencers. Little to none of the 2022 advertising spending has gone to the only two remaining private print dailies still being published in Yangon, Standard Times and Eleven, in great part due to their coverage which consumers consider biased and pro-military.

As a result of widespread audience growth, there has also been some social media revenue resurgence in 2022. Yet by mid-year, the advertising and media sectors were again hit by currency and import crises. As Facebook and Google only accept US dollars, for example, local businesses have faced devastating exchange rate losses. Facebook was far and away the most popular social media platform in Myanmar prior to the coup and since the coup it has been illegal; people have nonetheless continued to use it via Virtual Private Networks (VPNs), including placing advertisements on it.

According to local advertising executives, the advertising environment remains unclear so it is hard to make predictions. The only thing that is clear is that there is no advertising available for independent media covering the miltary coup.

In the essay below a senior national media executive reflects on the experience of launching a brand new outlet inside Myanmar in the post-coup period, and then moving it into exile.

Launching a new media business post-coup

I remember when exiled media came back to Myanmar in 2012. I was 28, and I’d already been working at a national media company for 10 years. I was proud of our work, but it was challenging, especially dealing with pre-publication censorship. We also had a hard time publishing anything deemed negative, including fires and floods. Compared to us, exiled media had a lot of freedom and a lot of local journalists worked for them. We had the same abilities as the exiled media, but our conditions and constraints were very different.

I had no idea that 10 years later I would also end up in exile.

Soon after the February 2021 coup, the military revoked my media company’s licence and the owner decided to shut it down. It was such a huge blow for those of us working there. But we didn’t want to give up, so some of us got together and launched a new underground media. Our plan was to stay inside the country, but after working undercover for seven months and grappling with mounting security concerns, we decided to leave. We confided in some of our trusted colleagues. We made it clear that it was a personal decision and that we would try to help them if they also wanted to go. In the end, though, they decided to stay inside. It was their choice, but I still feel guilty that I’m no longer facing the same risks as them.

When we were working together on the ground inside Myanmar, it was much easier to manage the team, assign stories, and communicate. When we want to assign stories now, we really need to think about whether or not we should do it. That’s because our understanding of what’s going on inside has changed. The constant barrage of news can feel so overwhelming and we sometimes find ourselves overreacting. It’s so hard to judge from afar and we know this can make us overly-cautious. If our reporters are on assignment, for example, and we hear really bad news, we tend to get nervous and ask them to go home. In the end, though, we know our team really well. They’re very experienced, and we trust them. So if they tell us it’s safe to continue, we follow their lead. As long as they remember that safety and security come first.

Despite our efforts, though, we find it hard to enforce good security protocols. Many people send us footage and information via Facebook Messenger. We’ve told them over and over again to use Signal or Viber, but they’re used to Messenger and think that deleting messages will somehow keep them safe. We keep telling them it won’t, but so far that hasn’t changed their behaviour. On our side, we have to be very careful about the messages and videos we receive as a lot of them are fake.

Launching a media business underground and anonymously has been a real eye-opener. Think about it. If no one knows who you are, you can’t rely on your history, reputation or brand. We were forced to start at zero. Even talking to our sources was a struggle when we first got underway.

The good news is we’re succeeding. We’ve managed to build a brand built on strong journalism. And that means our digital audiences are skyrocketing. We can’t compete with the quantity of stories some other outlets are producing, but we can compete when it comes to quality. One of the reasons for our success is that we only work with trusted staff members. We don’t use any freelancers or citizen journalists. And we’ve discovered a good thing about being in exile. It’s often easier and safer to communicate with sources inside from the outside, and that means we’re able to focus more on high quality content.

Sometimes we feel we’re not moving fast enough and that our content isn’t as good as we’d like. We find that really painful. We’ve also had to learn about donors and funding for the very first time, and to come to terms with the harsh reality that we’re dependent on them. But we’ve also noticed more and more people talking about us and sharing our stories, and our audience is growing faster than we ever imagined. That’s why we keep going.

Nway Oo, senior Myanmar media executive

Survey results and analysis

We stayed as long as we could and then made the tough decision to shut down our media inside the country and to set up a new media in exile.

Senior Myanmar media executive

Based on interviews with 32 senior media executives, the charts in this section explore the post-coup reality of Myanmar independent media outlets, including operational status, location, impact, opportunities, decision-making, lessons learned, staffing, digital audience growth and investment, commercial revenues and grants, the challenges associated with operating media businesses on social media platforms, and future priorities.

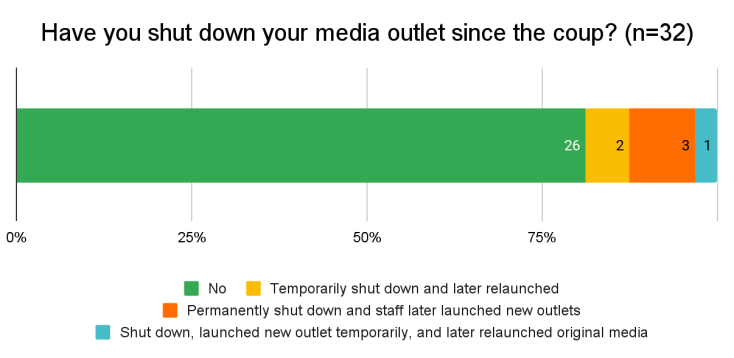

The first chart, below, looks at the status of the 32 media outlets interviewed: 26 of these outlets have continued operating with no interruptions; two temporarily shut down and later relaunched; one shut down, temporarily launched a different outlet, and then relaunched its original outlet; and four outlets permanently shut down and their staff later launched new outlets.

We made the right decision not to shut down our cross-border office in Thailand and that made us quicker and safer when the coup happened.

Senior Myanmar media executive

Since the coup, all but one of the outlets have moved their central operations to a new location. Eight are now located inside Myanmar in areas controlled by the military, two are in areas protected by ethnic armed organizations, seven have cross-border operations, 11 are currently in exile in countries bordering Myanmar, three are in exile in third countries, and one has multi-country operations. The one outlet that is still operating above-ground in its traditional location in an area currently controlled by the military is no longer publishing political content.

Impact, Opportunities, and Lessons Learned

Staff have been harassed, detained, tortured and imprisoned.

Senior Myanmar media executive

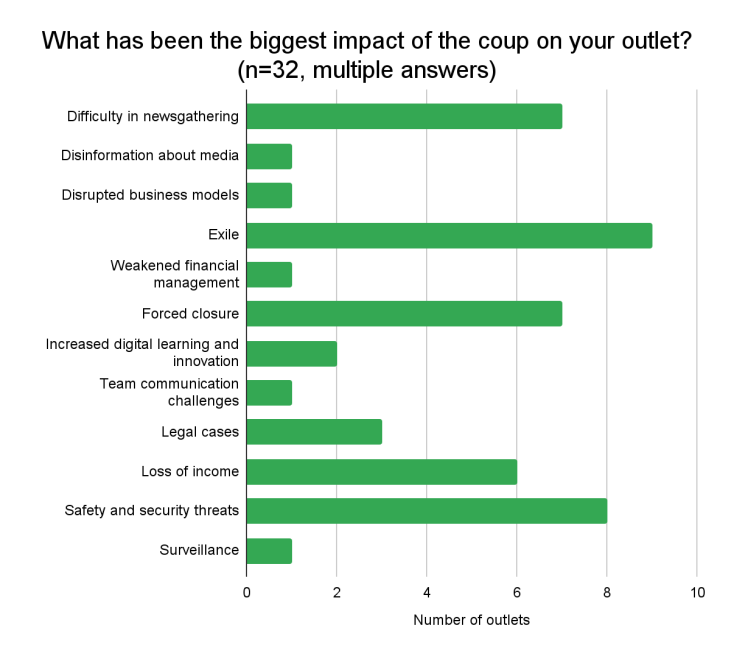

The next five charts tackle a variety of questions relating to the post-coup period, including impact, opportunities, decision-making, lessons learned, and hindsight. In response to the first question about the biggest impact of the coup on their outlets, the respondents offered a range of answers, including exile, safety and security threats, forced closure of their media outlets, news gathering difficulties, increased digital learning and innovation, loss of income, and legal cases.

To keep our staff and their families safe and secure, we’ve had to completely change the way we function and communicate

Senior Myanmar media executive

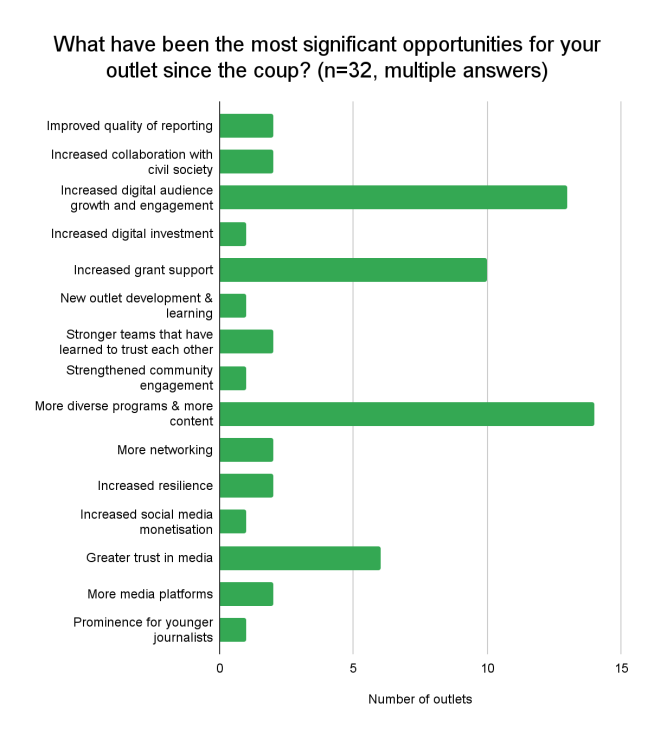

The next chart details the outlets’ most significant opportunities in the wake of the coup, including increased digital audience growth and engagement, greater grant support, more diverse programming and content, and increased trust in media. During their interview, one national senior media executive also added, with a note of sadness, that due to outlets shutting down and journalists fleeing into exile, there are now a lot of experienced media people looking for jobs so it is an excellent time to do head-hunting.

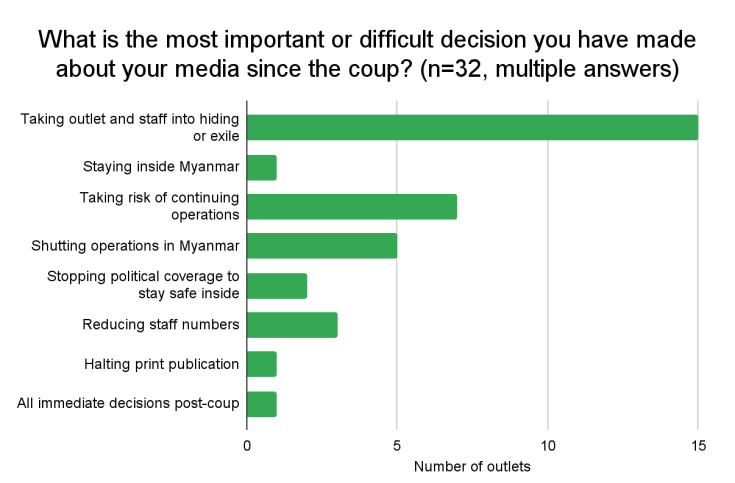

For the following chart, the 32 senior media executives reflected on the most important or difficult decision they had made as a result of the coup. Their answers range from taking their outlets and staff into hiding and exile, to continuing their media operations, to shutting down their operations inside Myanmar, to letting their staff go. One senior national media executive noted that it was a very difficult decision to stop their print publication and that they still missed it, while an ethnic media senior executive said that they had also given serious consideration to stopping their print, but decided their audience still needed it. The latter outlet has continued to print a reduced number of copies using a printing house in Yangon.

We helped staff flee to the protected border areas without knowing what would happen and how long they’d be there.”

Senior Myanmar media executive

We’ve hired more young reporters and they’re helping us develop new digital content and platforms, and attracting younger audiences. We’ve learned that we need to really listen to them and respect them.

Senior Myanmar media executive

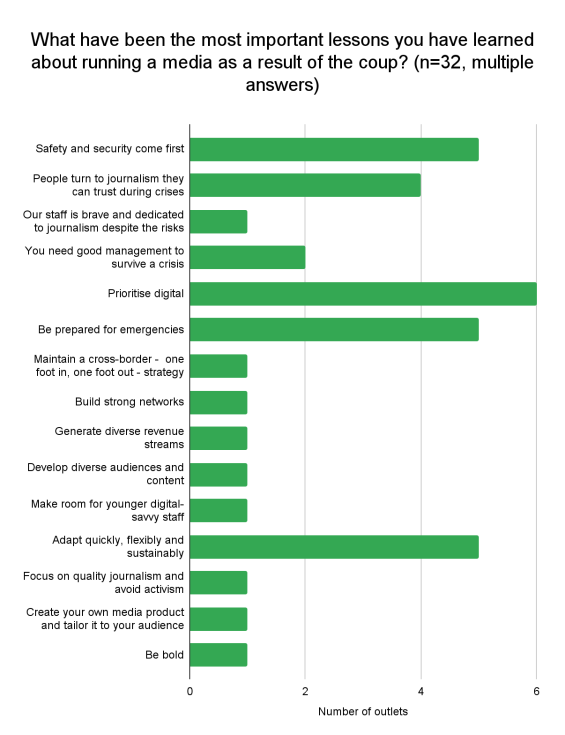

The next chart looks at the most important lessons the senior media executives say they have learned as a result of the coup. Once again, there are a variety of answers, including the importance of prioritizing digital, putting safety and security first, always being prepared for crises and emergencies, adapting quickly, flexibly and sustainably, and putting good management into place as “without it, you cannot survive crises”.

We weren’t prepared for the coup. That placed our staff and our media outlet at far greater risk.

Senior Myanmar media executive

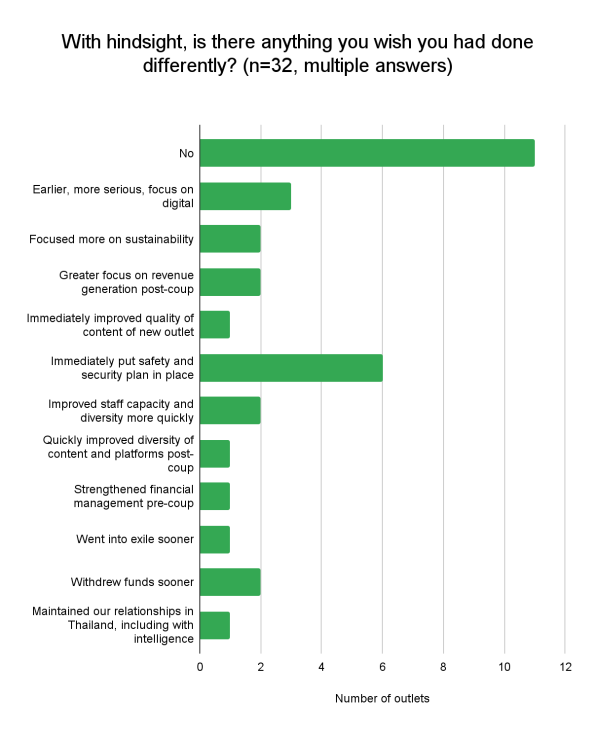

For the next chart, the senior executives interviewed reflected on whether, with hindsight, there was anything they wish they had done differently. Eleven of the 32 responded that they were happy with their actions and decision-making and would not change anything. The other 21 cited a variety of regrets, including wishing they had adopted an earlier and more serious focus on digital, immediately put a safety and security plan into place, improved staff capacity and diversity, withdrew their money as soon as the coup happened, and placed a greater focus on sustainability and revenue generation.

Human resources

The coup has taught us that our staff is extremely loyal and passionate about journalism and serving their community. Despite the huge risks they want to continue working.

Senior Myanmar media executive

The three charts in this section take a look at human resources, including size of staff, changes in staffing since the coup, and the status of in-country staff. The first chart, below, aggregates staff size data: two of the media are large (70-150 staff), nine are medium-sized (20-69 staff), and 21 are small (1-19 staff).

Letting go staff has been one of the most painful decisions we’ve had to make in the wake of the coup.

Senior Myanmar media executive

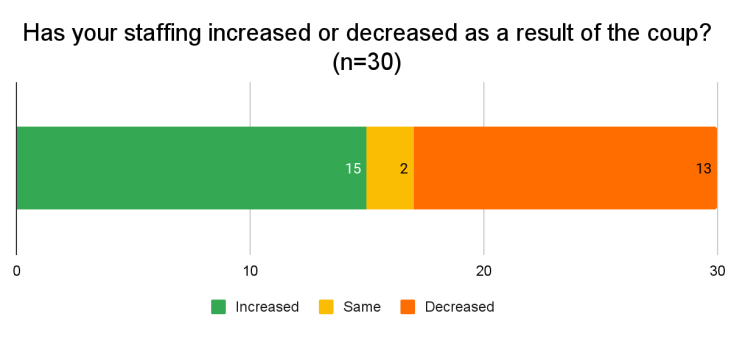

For the next chart respondents were asked if their staff numbers had increased or decreased since the coup. Close to half – 15 – say their staff has increased in size, 13 say that it has decreased, and two that their staff numbers have remained the same. There are 30 respondents for this chart, instead of 32, because two of the media interviewed were created post-coup.

We can’t always get what we want from people on the ground. Some are more concerned about the revolution than their reporting. And we feel guilty being in a safe place and asking them to do risky work. If we’d stayed inside, it would have been easier to manage our teams.

Senior Myanmar media executive

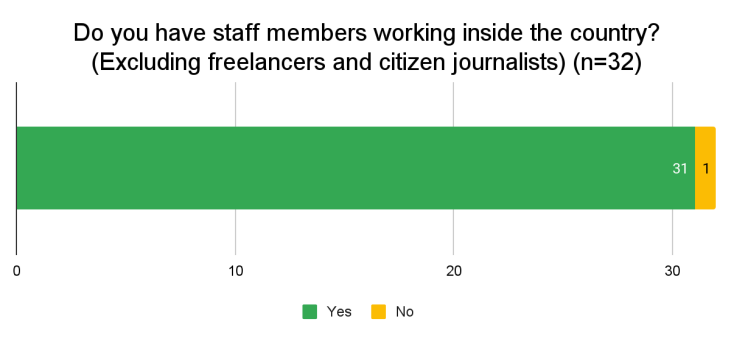

The final chart in this section, below, shows that 31 out of 32 senior media executives have staff members working inside Myanmar. Twenty-four of the respondents say they also work with freelancers, which some also refer to as stringers, and citizen journalists (CJs). There seems to be a widespread understanding that freelancers have journalistic training and/or experience, and are paid, whereas citizen journalists do not necessarily have experience or training, and are not paid, yet, in reality, the distinction between the two groups is not clear-cut. One senior national media executive expressed the opinion that since the initial post-coup emergency period has passed, the time for CJs has also passed, and that it was now time for experienced journalists and serious journalism.

Digital audience growth since the coup

Everyone who has access to wifi is online and looking for news, or asking people they know to look online for them.

Senior Myanmar media executive

All of the 32 senior media executives who were interviewed for this report say their outlets have experienced significant audience growth since the coup. The four media that launched new outlets in the wake of the coup, and therefore were starting from zero, experienced particularly strong initial growth.

The seven charts in this section look at total average digital audience growth since the coup; disaggregated audience growth for Facebook followers, YouTube subscribers, and website visitors; the reasons why digital audiences have grown; and investments in digital since the coup, including platforms, content and skills development.

The first chart looks at total average digital audience growth since the coup. The chart shows steady average growth across all platforms, although it is the strong YouTube subscriber growth that stands out, followed by the notable Facebook audience growth. There are a variety of reasons that help to explain the significant YouTube growth. More outlets have been focusing on YouTube content post-coup, in part because Facebook is illegal inside Myanmar but also because there is strong demand for video content by audiences wanting to not only read, but also see, what is happening around the country. As a result, the quality and quantity of YouTube content is increasing. Also, YouTube is legal inside Myanmar and does not require a Virtual Private Network (VPN), and this makes the platform faster to use. Media are also increasingly recognizing YouTube’s potential for monetization; those that have been able to grow their YouTube audiences are sometimes generating significant revenues and are consequently motivated to further focus on development of this platform.

The chart shows the average negative website growth that media have experienced since the coup. Websites have never been a particularly popular platform in Myanmar, and that trend has been exacerbated in the post-coup period. One reason for this is the impact of whitelisting, when junta officials only allow access to approved websites and platforms that are on a ‘whitelist’. Myanmar audiences also tend to be reluctant to check websites because of the additional data charges they will incur; by contrast, access to Facebook is often included in internet service packages. These two factors, in addition to cost considerations, also serve as a disincentive for media to invest in website development. This explains why MDIF was unable to access website data for all interviewees; as a result, the sample size for the website analysis is smaller than for the more popular social media platforms.

The chart below looks at average Facebook follower growth since the coup. The average for all outlets shows steady, significant follower growth. But when the data is disaggregated, it is regional media that show the most dramatic growth by far – an impressive 260%. Likely reasons for this include: two of the regional media set up new outlets in the post-coup period and subsequently experienced significant growth; there has been extensive conflict in Myanmar’s seven regions since the coup, likely leading to a high demand for news and information; and regional media are now producing more high quality videos. Ethnic media outlets show the next highest level of Facebook follower growth: on average their numbers grew by 140% by mid-2022.

The next chart, below, looks at average YouTube subscriber growth since the coup. The sample size is 26 because MDIF did not have access to all 32 sets of YouTube data. The data shows significant and steady average growth across all outlets. National media growth is greatest, averaging more than 400% growth in YouTube subscribers since the coup. Ethnic media outlets showed less dramatic, but nevertheless steady, growth, reaching 120% growth since the coup as of July 2022. By contrast, there was little to no YouTube subscriber growth in 2021 for regional media, although that trend significantly shifted in 2022, with strong upward growth, bringing average growth since the coup to an impressive 320%. This upward trend can in part be attributed to: the significant growth of one of the five regional media outlets; that two of the regional media developed strong video production teams as of late 2021; and that these media are among the very few outlets publishing up-to-date reports about conflict in central Myanmar.

The following chart looks at average website visitor growth since the coup, disaggregated by media type. Given that many of the media do not have a website and that MDIF did not have access to all of the interviewees’ website data, the sample size for this chart (n=11) is comparatively small. The chart shows a downward average trend for all outlets, with some spikes, and all media are showing negative growth as of July 2022, compared to their pre-coup levels. Historically there has been much more significant audience growth on media’s social media platforms, and this has remained the case in the post-coup period; this also explains the average downward trend for websites. The spikes can largely be attributed to data from two of the national and ethnic media outlets whose website visitors rose on several occasions, particularly during the April-June period when coup related crackdowns intensified, the National Unity Government (NUG) was created, and civilian resistance grew, and then again in the September-November period when there was again substantive coverage of civilian resistance and ethnic armed organization solidarity in anti-coup efforts. By comparison, regional media outlets experienced an immediate steep drop following the coup, in large part because their websites were inactive while they tried to determine how to respond to the crisis. Since mid-2021, however, they have been steadily climbing again, although they are still below their pre-coup visitor levels.

While the newer outlets experienced immediate, significant audience growth on Facebook in the wake of the coup, compared to the older media, their YouTube subscriber growth was negligible. As well, while the number of website visitors to the older outlets has been plummeting, the post-coup outlets are still growing their website audiences.

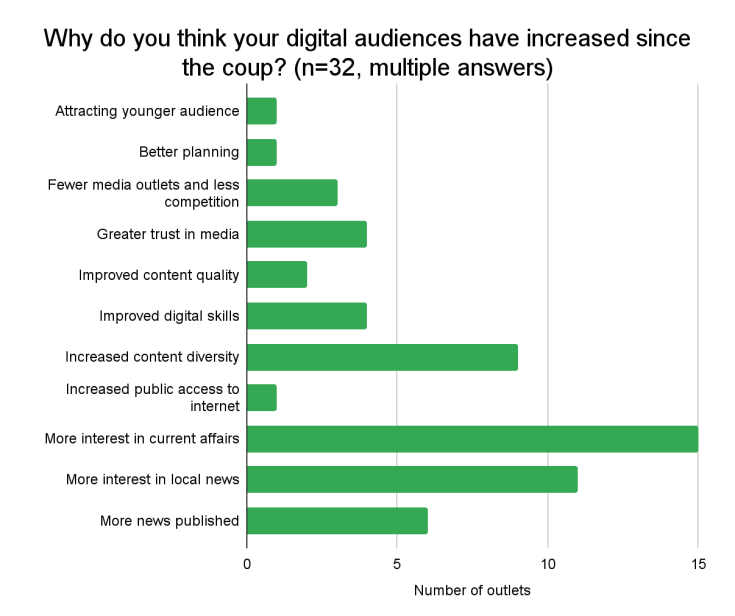

We asked the 32 interviewees to reflect on why their digital audiences have grown so dramatically since the coup. The reasons cited in the next chart include an increased interest in current affairs and local news, a greater quantity of news being published, a greater diversity of content, and a greater trust in media.

Even elected officials who criticized our coverage before the coup now come to us for credible news and information.

Senior Myanmar media executive

We should have taken our digital platforms and digital security far more seriously long before the coup.

Senior Myanmar media executive

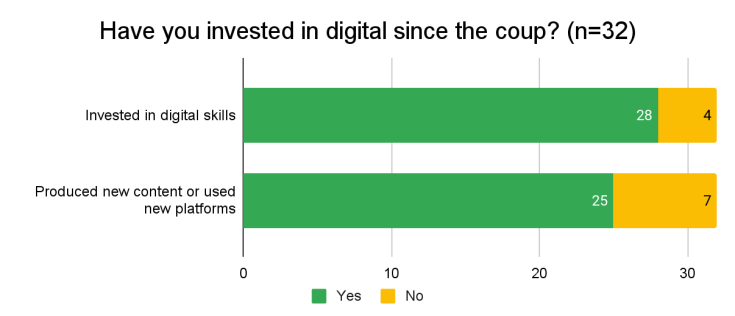

The next chart looks at digital investment since the coup. The vast majority of interviewees confirm that they have invested in digital skills development, and more than 75% have also invested in producing new types of content and using new platforms. Many say that the coup has forced them to finally take the digital space seriously; this includes learning how to use tools to grow their audiences, digital security, digital monetization skills and tools, and understanding digital analytics. With hindsight, some admit that they had many opportunities to do this in the past, but did not fully embrace them or take them seriously enough. The space has become more complex in the post-coup environment, due, among other things, to more stringent standards being applied by social media platforms, so they also acknowledge that they have had to face a very steep learning curve during a time of crisis to try to avoid being penalized by the platforms for violating these standards.

We were tackling more diverse editorial topics before the coup, including social and land issues, and legal reform. Since the coup, though, our content mainly centers on conflict. The coup-related news is overwhelming and our audience wants to hear it. But sometimes it makes us feel trapped.

Senior Myanmar media executive

The interviewees point to the variety of content they have started to produce following the coup: short video content for TikTok; radio news packages; news features; local and international news programs; podcasts; documentaries; e-books; video news and feature packages; daily tv news; business stories; women’s programming, including Rohingya women; LGBTQ+ stories; agriculture; consumer needs; health; the impact of the coup on people’s lives; revolutionary poetry; more local language content; more community news (via mobile journalism training of a new citizen journalism network); conflict and IDPs; and Junta Watch.

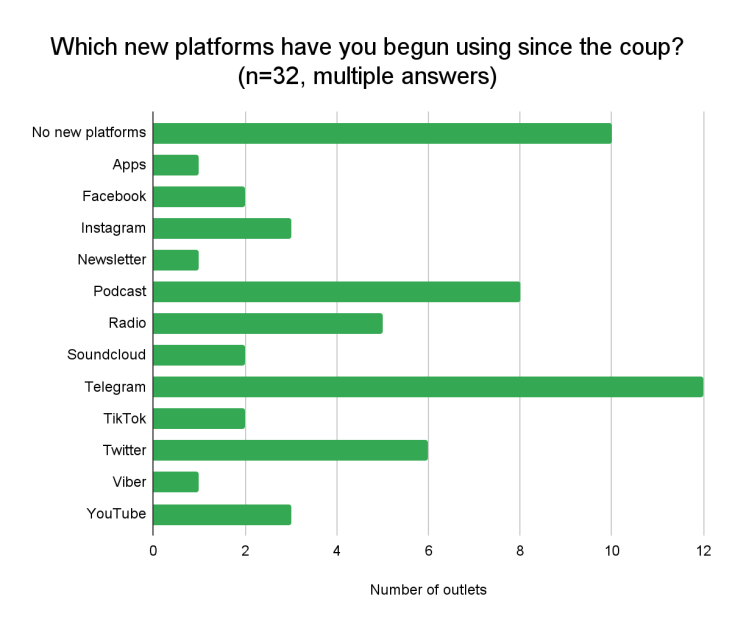

The next chart looks at the new platforms adopted by the interviewees since the coup. While 10 interviewees say they are not using any new platforms, 22 of them are posting on a variety of platforms that they had not previously used.

Our focus on print media made things much tougher for us when the coup happened. We had a lot of digital catching up to do.

Senior Myanmar media executive

Post-coup commercial revenue development

Because of the coup we’ve lost the commercial revenue that we worked really hard to build. That’s forced us to change our business model.

Senior Myanmar media executive

The commercial revenue of independent media was very hard hit by the coup. In this section we look at the ways in which media outlets are currently financing their operations, and at the opportunities and challenges of running independent media businesses on social media platforms in the post-coup context. As a first step, the 32 Myanmar media executives interviewed shared details about their current commercial revenue.

In this report, current commercial revenue includes: commercial advertising; content sales to other media; donations; co-working space rentals; data agency client reports; Doh Athan podcasts (Hirondelle/Frontier); Facebook Instant Articles, Stars, Instream Ads; live event broadcasting; Public Service Announcements (PSAs); Google Adsense; local business advertising; media editorial collaborations; membership programs; content service fees (radio); YouTube monetization; and television airtime purchases.

We should have worked harder to diversify our revenue generation and to think creatively in the pre-coup period. I think that would have made us more resilient now.

Senior Myanmar media executive

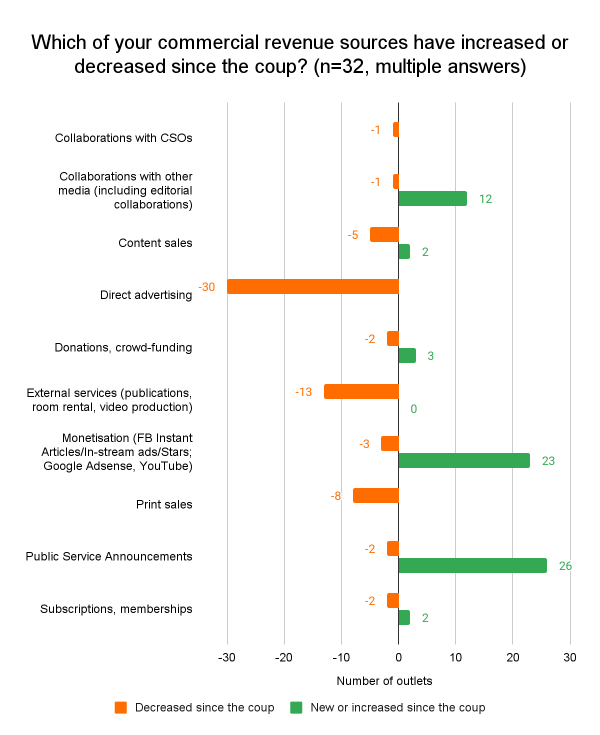

The chart below shows which commercial revenues interviewees say have increased or decreased since the coup. There is a comparatively significant increase in collaborations with media outlets, PSA partnerships, and social media platform monetization, for example, as well as a significant decrease in direct advertising, print sales, and external services, such as publications and video production.

Operating media businesses on social media

You need to take Facebook community standards seriously. We didn’t, and when our page got shut down following the coup it disrupted our work and had a negative impact at a very important time.

Senior Myanmar media executive

Prior to the coup, many media were unable to access digital revenue opportunities on Facebook and YouTube, largely because they had not sufficiently invested in digital and therefore did not have a strong digital focus or enough audience subscribers, followers, and traffic to become eligible for social media monetization. Yet as illustrated in the ‘Digital audience growth’ section of this report, those circumstances quickly changed in the wake of the coup, with most private media experiencing dramatic digital audience growth which in turn made them eligible for monetization. Aggregated revenue data from eleven of MDIF’s media partners (2 national, 5 ethnic, and 4 regional) paint a picture of this post-coup trend. While prior to the coup, only four of the 11 media were eligible for monetization, in the wake of the coup they have all become eligible. All eleven of these media are currently monetizing their content on Facebook, and 10 are doing so on YouTube; in almost all cases they are earning higher revenues on the latter platform.

While these monetization opportunities are generally welcome, earnings are often quite modest and cover a very small proportion of operating costs. It is also risky for media to be so reliant on social media platforms; if platform policies are not adhered to, digital revenue streams can be dramatically reduced or even stop entirely. This is why two of the national media senior executives interviewed explained that they wanted to reduce their reliance on social media revenues and focus their energy on membership programs and other forms of offline revenue generation.

The five charts in this section look at: social media revenue as a proportion of total commercial revenue since the coup; average total commercial revenue percentages in 2021 and 2022; average total social media revenue percentages in 2021 and 2022; average total social media revenue percentages since the coup; and social media revenue and non-social media revenue as a proportion of total operating costs in 2021 and 2022. This section focuses on commercial revenue which does not include grants.

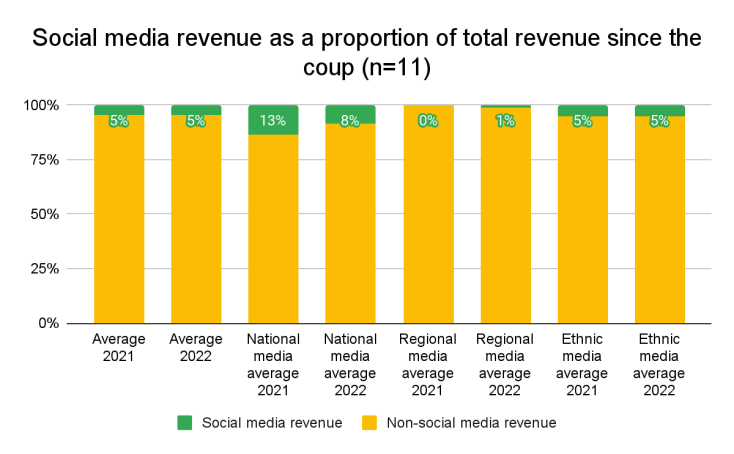

The first chart, below, looks at social media revenue as a proportion of total commercial revenue since the coup. The data shows that the revenue earned from social media platforms constitutes a very small percentage – 0-13% depending on media type and year – and that the media are earning most of their revenue from non-social media platforms. The latter revenue from non-social media platforms includes content sales (podcasts, TV, radio, etc), donations, membership programs, and advertising (PSAs, and in one rare case, local business advertising). In many of the cases, the PSA initiative launched by MDIF, and now complemented by three other organizations, constitutes the most significant non-social media commercial revenue source. When comparing 2021 and 2022 results, please note that in January 2021 (pre-coup) the media in the sample were earning higher online and offline revenues than after the coup. Also, the 2022 data only covers the first six months of the year (January-June) and has been extrapolated as a projection for the remaining months.

In the chart above, average social media revenue as a proportion of total revenues for all 11 media outlets is 5% for 2021 and 2022. Only one of the two national media included in this sample was earning social media revenue in 2021, covering a total of 13% of its total costs; in 2022, when both are earning social media revenue, their aggregated earnings represent an estimated average of 8% of their total revenue. By comparison, for the five ethnic media earning revenue, social media revenue represents an average of 5% of their total earnings for both 2021 and 2022. Only one of the four regional media partners earned social media revenue in 2021, but it was so small that they did not impact on the percentage, which therefore remains 0. Two of the other outlets had to shut down their media and set up new platforms which prevented them from earning social media revenue; the fourth media was eligible, but became embroiled in a Facebook community standard violation dispute which prevented them from earning revenue. In 2022, all four regional media have been earning social media revenue for at least part of the year, but this represents on average just 1% of their total revenue. The trends for national media and ethnic media are similar for both years and provide a more positive outlook than that of the regional media; this is consistent with past trends. One of the reasons is that national and ethnic media are in most cases better established and experienced than the regional media, including with regards to capacity, larger audiences, and stronger content; they also historically have more access to donor support and technical assistance.

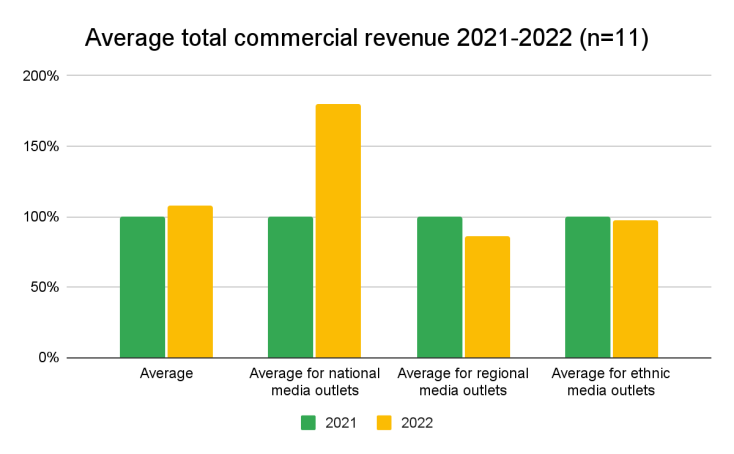

The next chart looks at the average total commercial revenue for 2021 and 2022. 2021 revenue is shown as 100% for each type of media outlet in order to compare growth over 2022. When data is aggregated it shows a slight average increase in 2022 for all surveyed media. This could be linked to the fact that the two national media outlets surveyed are experiencing significant overall revenue growth in 2022. The revenue for the five ethnic media are more or less consistent for both years, with a tiny drop in 2022. The four regional media outlets also show a drop in revenue in 2022; in their case, it is a slightly larger drop. Please note that this chart includes projections until the end of 2022.

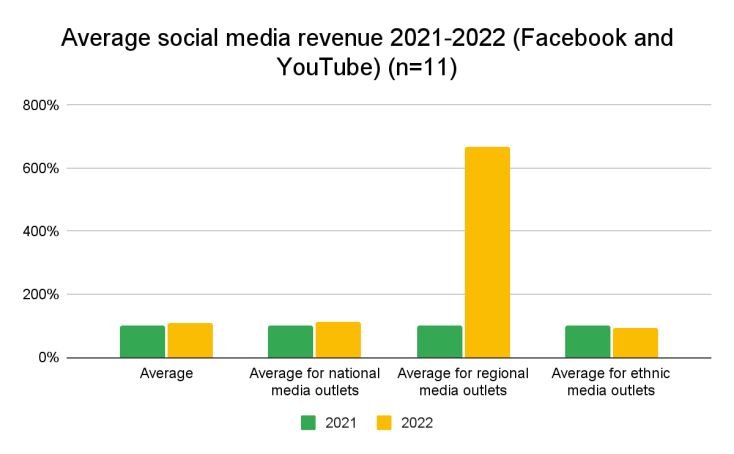

The next chart (below) looks at average social media revenue (Facebook and YouTube) in 2021 and 2022; this includes, for 2022, projected revenue for August-December 2022, based on actual revenue in the first half of the year. 2021 revenue is shown as 100% for each type of media outlet in order to compare growth over 2022. According to the chart, there is a very slight increase in average social media revenue for 2022. When the data is disaggregated, there is also a very slight increase in average social media revenue for the national media. For ethnic media, there is a very slight drop in average social media revenue in 2022, in part because one of the five ethnic media stopped its video production and therefore lost its main social media revenue. The regional media experienced the most significant average social media growth in 2022 by far; this is because almost all of these outlets started accessing online monetization for the first time in 2022, though the increases have not yet been that meaningful in absolute terms.

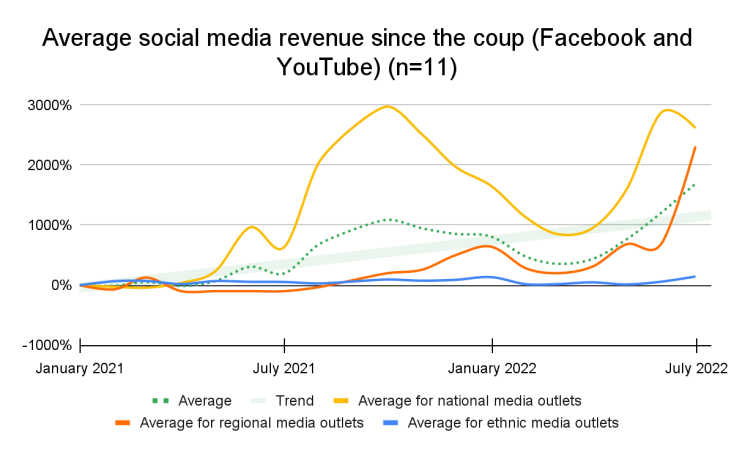

The following chart looks at average social media revenue progression since the coup for the 11 media in the sample, and also disaggregates the data to illustrate the comparative progression of national, ethnic and regional media outlets. The chart indicates a small but steady upwards progression average for all the outlets through most of 2021, with a modest dip in early 2022, and then significant growth far beyond 2021 levels. For ethnic media outlets, there is modest growth throughout 2021 and 2022 because many of the ethnic media were already monetizing their social media platforms prior to the coup. By comparison, the regional media outlets showed little to no growth in 2021, and in some cases lost money, largely because some of the outlets shut down for part of that year, and then their staff had to launch new outlets. In 2022, the regional outlets showed modest average growth over the first months, and then significant average growth as of mid-2022 when they began monetizing their content, most of them for the very first time. The national media average growth, with dramatic peaks and troughs, can be largely attributed to one of the national outlets; the peaks appear to be linked to periods of strong video reporting, and the one dramatic drop to a period when the outlet was reorganizing and therefore focusing less on its video content production.

The next chart looks at social media revenue and non-social media revenue as a proportion of operating costs since the coup. It indicates that the average social media revenue over two years (including projections until the end of 2022) cover a tiny proportion of operating costs, ranging from 0.9% in 2021 to 1% in 2022. When the data is disaggregated, the national media proportion ranges from 0.7% in 2021 to 0.8% in 2022; for ethnic media, from 1.7% in 2021 to 1.4% in 2022; and for regional media, from 0.1% to 0.6% over the two years. The slight drop in 2022 for ethnic media can likely be attributed to one of the outlets ceasing its video production.

The chart shows that independent media are struggling to make significant revenue from the monetization of their social media platforms despite the growth of their audiences. The non-social media commercial revenue includes content sales (podcasts, TV, radio, etc), donations, membership programs, and advertising (PSAs, and in one rare case, local business advertising). With regards to grants, the two national media surveyed benefited the most, largely because one of them is running a larger, more expensive operation and is the recipient of a variety of grants from diverse donors. Compared to the four regional media, the five ethnic media also receive a significant amount of funding. According to the chart, the regional media are earning comparatively more non-social media commercial revenues; for the most part, these come from PSA partnerships.

Karen Information Center (KIC) is one of the rare media able to cover a comparatively significant percentage of its operating costs via the business revenue it generates on its social media platforms in the post-coup period. MDIF’s coach, Tosca Santoso, started working with KIC on its business development in 2015; in his essay below he reflects on how KIC has been impacted by, and responded to, the coup.

Seizing unexpected opportunities during a crisis

Crises often create unexpected paths forward. After 25 years running a media outlet in a turbulent ethnic state, this is something the Karen Information Center (KIC) knows all too well. As a result, when the military coup happened on 1 February 2021, the team was prepared to take action quickly and decisively.

Their challenges were nonetheless enormous. For many years, the KIC team relied on a monthly print journal to reach their diffuse audience. Prior to the coup, they were printing around 2,000 copies a month. Their distribution network was geographically and logistically complex, so it always took a lot of effort to collect payment from the people who bought their journal. Then the coup happened and KIC was forced to abruptly halt its print productions. It was too difficult and risky to distribute the journal, not to mention to find a printing house that was safe to use. “After the coup most audiences were getting information from digital platforms, especially social media. At the same time, KIC’s overseas audience was keen to follow news, and they also got it from digital platforms,” explains Nan Paw Gay, KIC’s Director.

By focusing solely on digital platforms, and re-allocating its print resources online, in the post-coup period KIC has been able to produce more content and improve its quality. Its dramatic audience escalation has been triggered by heightened demand for news as a result of the coup, coupled with the reality that digital platforms are the only independent media options available to Myanmar audiences, other than television and radio.

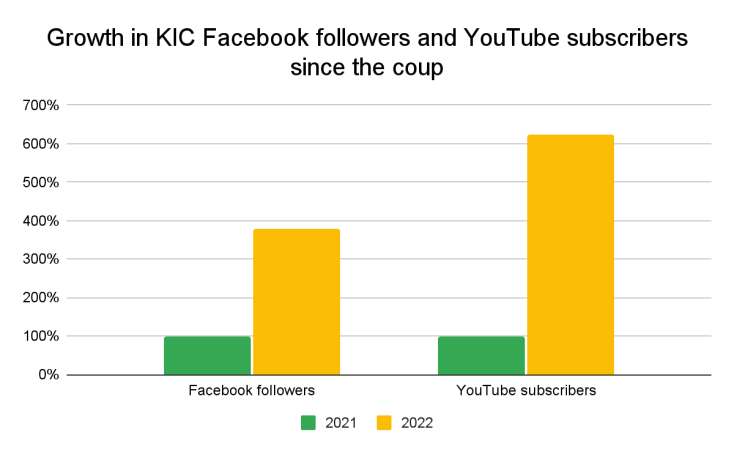

The numbers tell KIC’s story. Shortly before the coup, its YouTube channel had approximately 7,000 subscribers and 500,000 monthly views. Eighteen months later, in mid 2022, its subscriber numbers had shot up to 48,000 – a 600% increase – and its monthly views to one million. Over the same period, KIC’s revenue from YouTube increased almost threefold.

KIC has seen similar Facebook audience growth. Prior to the coup, it had almost 300,000 Facebook followers. By mid 2022, that number had increased to 1.2 million – a growth of almost 300%. Over the same period, its monthly Facebook reach increased from three to four million. KIC’s revenue from Facebook also increased, not only from Ad breaks (the short advertisements that appear before or during longer-form videos), but also from Facebook Stars, a feature that allows monetization of live streaming via Stars that viewers can buy and send during streaming. Revenue from social media platforms currently covers about 10% of KIC’s operating costs and is set to further increase in line with the growth of its audience. By comparison, before the coup KIC’s digital platform revenues covered less than 3% of its operating costs.

Since focusing on its digital platforms, KIC has received a lot of input from its audience via social media, including original photos and video content. This has helped the team expand and diversify their information sources, although it also means they need to be careful to filter out misinformation and disinformation. “We do quality control of all of the stories that go on our digital platforms,” explains Nan Paw Gay.

KIC has long cultivated a close relationship with its audience and community, and to build upon that solid base it recently launched a membership program. For a media to set up this kind of program, it needs to have a payment collections system, and to set that up it needs a company registration. Being exiled in a second country complicates that task. To solve this issue, at least on the short term, KIC decided to work through the online payment collection system Facebook Subscriptions. While it is far from a perfect solution to link its membership program to Facebook, it is allowing KIC to move forward while it tries to set up a more independent and sustainable system.

Being forced to become fully digital has increased KIC’s digital reach and revenue. It has also propelled KIC to create a membership program that enables its audience to help support its journalism and operations. This means KIC has been able to turn the major challenges presented by the coup into significant opportunities for growth.

Tosca Santoso

MDIF business coach

The “Seizing unexpected opportunities during a crisis” essay highlights the Karen Information Center’s success in generating comparatively significant digital revenues on its social media platforms in the post-coup period, compared to the other outlets included in this research. Unfortunately, KIC is only one of a handful of outlets in this situation, and most of these outlets share a common history that includes exile and cross-border work – experiences that have enabled them to maintain and build teams, resources, systems and audiences outside of Myanmar which they have capitalized upon in the post-coup period.

Challenges and (imperfect) solutions for media operating on social media platforms

Monetization Limitations

Although Myanmar media outlets’ digital audiences and reach have generally skyrocketed since the coup, allowing nearly all media to meet the minimum engagement thresholds to access monetization, they regularly face restrictions in their ability to monetize on social media platforms. One of the main reasons for this is that platforms are refusing access to their monetization programs if publishers have a presence or bank account in Myanmar, or if they distribute content in Myanmar languages.

Prior to the coup, Facebook allowed monetization; Google did not, and since the coup it has tightened its restrictions. Given that revenues from these platforms represent an important opportunity for independent media in Myanmar to generate revenue, until this issue is resolved they feel obliged to try to find their own ways to bypass these restrictions.

Those media that are successful in reaching monetization threshholds then face further barriers to benefiting from this because their content frequently gets classified by the social media platforms’ automated detection systems as either violating content policies or lacking in originality. These content restrictions are justified by the platforms on the basis of their commitment to advertisers, who are asking platforms not to show their advertisements alongside content that is deemed violent or at risk of violating copyright. In cases where media are subjected to repeated content-level restrictions, they either risk being prevented from registering for monetization in the first place or else, if already eligible for monetization, may have that eligibility withdrawn and lose their access to monetization altogether.

Copyright

Myanmar media also regularly face copyright issues. Content produced by independent media is frequently used without permission by a variety of clickbait actors and either reposted wholesale or else repurposed and posted on their own social media pages or digital platforms as if it is their own original content. These clickbait entities often have a sophisticated understanding of platforms’ algorithms, as a result of which they are able to generate larger reach and revenue from this output compared to the media that actually produced the original content.

Some of these actors have also taken to impersonating certain media, repurposing their content and occasionally their brand to maximize their revenue. Media such as Mizzima, Khit Thit, and RFA have all been impersonated in this way. Even 7Day which, prior to the coup, was one of the country’s most popular media, has had its brand hijacked in this way, even though the media shut down soon after the coup so does not actually exist any more.

The numbers of spammers distributing stolen content for financial gain is growing and is making the digital space and the copyright problems increasingly complex. Yet, until now, neither Facebook nor YouTube have found a solution to this issue.

The enormous dangers of newsgathering in Myanmar means that media outlets are frequently reliant on the work of freelancers and citizen journalists who may sell the same footage and photos to more than one media outlet. This apparent duplication of content can often flag a copyright question and can lead to content removal, distribution reduction, and monetization restrictions. This problem is particularly prevalent on YouTube, resulting in Google rejecting the monetization requests of several independent media on the basis of lack of content originality. Some media have also reported facing copyright problems after selling their own footage or images to larger international outlets, such as the BBC, that have access to advanced systems to enforce their copyright.

Distribution restrictions

The impact of the coup has also had a negative impact on Myanmar independent media’s ability to disseminate some content due to its graphic nature. In reporting on clashes between the military and armed groups, or other acts of violence, the media is often falling foul of social media platforms’ automated content moderation systems. These systems are built around policies which were not designed for times of conflict. This is especially true of Facebook, which is actively leveraging automation in Myanmar. As a result, Myanmar media regularly face content removal for violating policies around the posting of graphic violence as well as divulging personally identifiable information about an individual or organization. The publication of graphic content is a grey area in journalism; in the wake of the coup some senior media executives acknowledge that they have not adequately tackled this challenging issue in their media’s editorial guidelines.

The lack of nuance in determining what content should be removed can result in media accumulating multiple strikes which in turn can have a wider impact on their distribution. This includes restrictions on the recommendation of media pages and content being recommended to new audiences and, in extreme cases, to a media’s page, or their admin team, being banned from Facebook.

Some media outlets have reported self-censoring their content to prevent any chance that the platform will remove their posts, for example by blurring out the photos and videos they publish about the conflict.

Myanmar independent media outlets have further expressed concerns over Facebook’s ongoing shift towards limiting the recommendation of political, social and civic content – which could have an impact on their page distribution and limit their ability to reach new audiences. Forty-five Myanmar media and media rights organizations recently published a press release urging Facebook not to implement this planned newsfeed modification in Myanmar.

These issues are not specific to Myanmar. Ukrainian and Afghan media, for example, are likely facing similar challenges. In the Myanmar case, some progress has been made: for example, in an increasing number of cases Facebook is responding more quickly when independent media outlets are grappling with community standard and copyright issues, and is also responding to requests for training for media outlets on these issues. Yet the system is still not working effectively for independent media, and there are key questions that need to be substantively addressed. How should platform policies be changed to make them appropriate to Myanmar’s conflict context? How can platforms ensure Myanmar independent media have official access to monetization? How can platforms address misinformation and disinformation without harming legitimate content producers? There are also questions directly related to the independent media outlets: how can they more easily access information about platform policies, and communicate efficiently with platform administrators, and how can they pro-actively strengthen their team’s communications systems, ensure that all of their team members understand the policies of the platforms on which they operate, and establish strong and ethical in-house wartime editorial policies?

Looking forward

We have to accept that we can’t do our jobs like we used to. We’re no longer eyewitnesses on the ground, we can’t speak directly to diverse sources like we used to, and we can’t get the same kind of high-quality footage.

Senior Myanmar media executive

Only one of the 32 Myanmar senior media executives interviewed for this report said they were planning to shut their outlet, in their case due to financial concerns. The other 31 executives were unanimous in saying they would not give up and that they were already planning for the longer term. Yet they also voiced concerns, ““If we don’t manage our media organizations and our money properly, then we won’t survive this crisis or grow into strong media.” As the chart below shows, over the next year almost all of the executives say that financial support would be the most valuable assistance they could receive, followed by new revenue opportunities, and technical assistance.

While 31 out of 32 senior media executives stressed that financial support from donors and other media support organizations would be the most important type of assistance they could receive over the next year, they also provided specific examples of potential commercial revenue opportunities including: membership programs; donations from supporters and audiences; subscriptions; advertising revenue (both direct and programmatic advertising); Facebook and YouTube monetization; FM radio; TV; CSO/NGO collaborations; content production, sales, and syndication; PSAs; print; offline activities; English-language site monetization; podcasts; and investments.